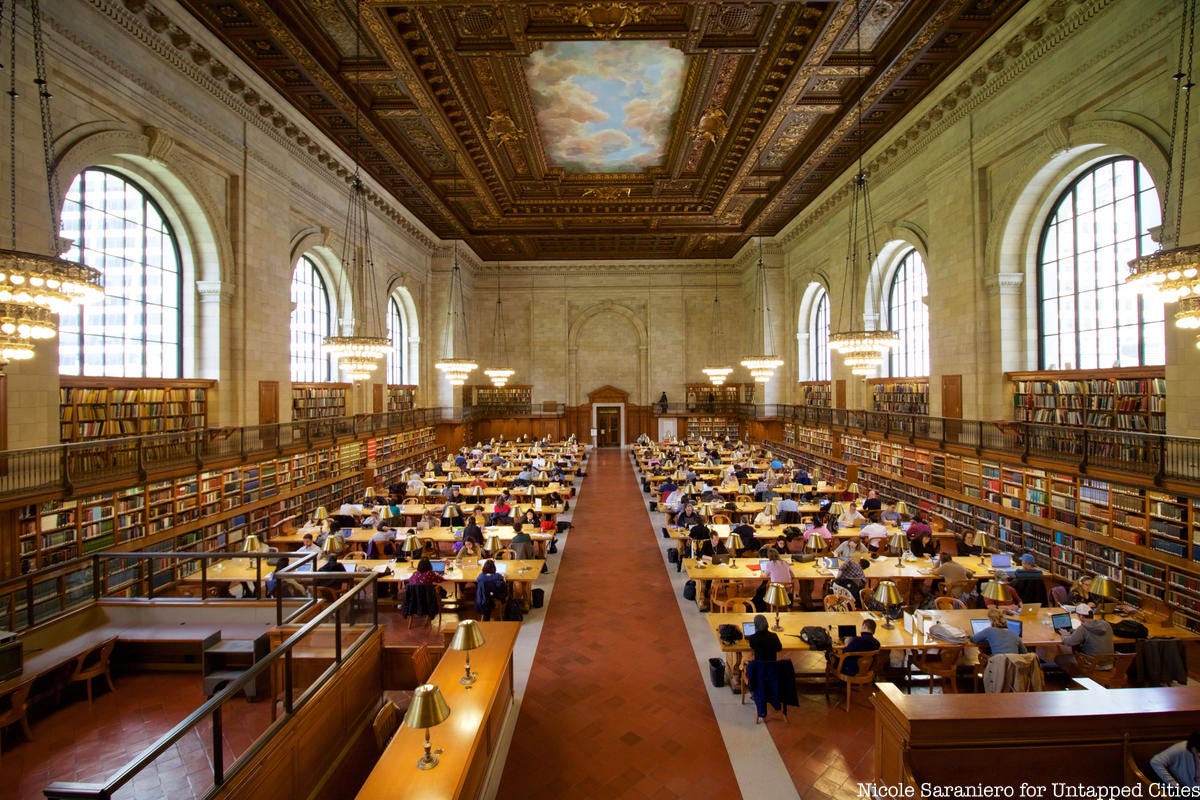

The deadline is fast approaching for writers to apply for the Cullman Center Fellowship at the New York Public library. Fifteen worthies who are working on projects that would use resources housed at the main branch of the library at Bryant Park with receive a $75,000 stipend, an office and all the research help they will need to work on a project from September to May.

It’s a genius idea to use the library to inspire and support literature and The Middlebrow, deep into writing a novel that draws heavily on New York history, considered applying. But, there’s no way to do it because The Middlebrow has a job. Most employers are not happy to have their workers disappear for 8 months and it’s hard to blame them.

The Cullman Center expects a full time commitment for those eight months, with the writers on site most days of the week, participating in library events, and limiting travel and outside business activities. They want commitment and that’s understandable. But it’s only possible for the small percentage of authors who are able to make a living selling books, and I see luminous names like Colson Whitehead, Sally Rooney, and Ben Marcus among its alumni.

This seems a common feature of creative grants in literature, non-fiction, theatre and others arts — there is very little support for people who, you know, work for a living. Now, you can say (and I'll agree) something like, “Well, heck, Middlebrow, maybe the Cullman Center is smart to invest in authors who can, you know, provably sell books and finish the projects they start and who are better writers than you are.”

Point taken, though I don’t get why you have to be so blunt about it.

“You’re a hobbyist,” you say, really letting me have it. “If you were a professional, you’d be able to make a living writing books and then you’d be free to apply for opportunities like this and accept them if you’re deemed worthy.”

Counterpoints:

First, there are a lot of talented people with great ideas, follow-through and talent who could make great use of resources offered by the Cullman Center on a part-time basis, while keeping the jobs that sustain their families and help them relate to a potential audience because people who buy books and go to plays are generally people with jobs who might appreciate the work of artists who share their workday experiences.

On the economics, a lot of these professionals can’t really “make a living” writing and selling books either. Sally Rooney can. Colton Whitehead can. But even George Saunders, who received a coveted MacArthur grant teaches fiction for a living and and charges for his (excellent) Substack. Nobody called T.S. Eliot a hobbyist for working in a bank.

When you read through a lot of these grant opportunities you stumble on testimonials of artists who are grateful to have been freed up to do their creative work because the grant money means taking a break from adjunct teaching or subsidizes a book advance that wouldn’t be enough to cover their expenses on its own. The subtext here is, “without this grant, I might have had to get a job,” and the further subtext is, “and how horrible would that be, since I am a creative artist.”

The rest of us have jobs. Now, to be fair, refusing to get a job in the hopes of getting a five figure grant is not a life strategy. The Cullman Center picks 15 people from thousands of hopefuls. But having a day job doesn’t make an artist a hobbyist.

A modest proposal — it would be nice if some grant making organizations also created and funded part-time opportunities for professionals who could benefit from the endorsement of the grant making organization and resources for research, rehearsals and writing space that working people need to succeed in their creative efforts.

In the meantime, if you can swing the terms of a Cullman Fellowship, I urge you to apply. It looks like an amazing opportunity.

Programming note: The Middlebrow is take a short hiatus, returning on September 8th.