In a sketch for this week’s Saturday Night Live, Selena Gomez played a model who visits a bunch of high schoolers to proselytize for her profession. “I was the first generation of my family not to go to college,” she announced, to the delight of the posing students.

The Middlebrow knows a few college-aged people have chosen non-collegiate paths. None have pursued modeling. About a third of Americans have bachelor’s degrees, a stat that, if you’re like the Middlebrow, seems low because just about everybody you know went to college and graduated. People with degrees tend to cluster together. Also, they tend to perpetuate the degree chasing. Parents with degrees expect their children to get them too, right?

Or maybe something is changing, very subtly and not yet affecting the statistics.

The young adults Middlebrow knows seem to be banking on work experience to carry them into careers and they might be right. The Middlebrow once worked for a small public company, in the finance industry where college degrees are typically a ticket to entry, where the chief operating officer had dropped out of school but attained considerable wealth and stature. Heck, after the financial crisis, he got to participate in the takeover of a bank that was full of people with flashy credentials.

The Silicon Valley-driven fantasy from Bill Gates to Steve Jobs to Mark Zuckerberg is that degrees don’t mean much if you already know what you’re doing (or get very lucky).

On average, people with college degrees in the United States tend to out-earn their peers over a lifetime. A bachelor’s degree holder will typically make $1.5 million more than a worker with a high school diploma. People with degrees are also less likely to be unemployed for long periods. On the other hand, people with useful skills can out-earn people who were educated to make jokes about Sartre and postmodernism (and there’s nothing stopping an autodidact trade worker from picking up books and learning those same cocktail party gags).

Besides, when we dig into the notion of people with college degrees earning excess pay, we have to consider that this is the result of societal bias, the unreasonable expectations of corporate gatekeepers and irrational credentialism. The Middlebrow admits that for specific job performance, there might be more to a 3 month internship than a 3 month seminar about Greek tragedy.

The Middlebrow is also cautious of his own biases in favor of humanities education for the purpose of becoming “a well rounded person,” rather than to make money later. For one thing, the idea of education to form interesting people who become engaged citizens only “kind of” works. We all know people with degrees from good schools who don’t meet the standards of “well rounded” adults because so much depends on how you spend your time after school. The Middlebrow once worked for somebody who bragged of having no hobbies and devoting all non-work time to a child who she did not know she had named after a character in To Kill a Mockingbird. That’s not even a joke!

The other problem with the “well rounded” person defense of higher education is that it’s largely a motivation for the already wealthy student. If you’re all set in the family real estate business, you may as well go learn how to be interesting, right? After World War II, this was taken up by a lot of striving families and striving students and this is where the old “first generation of my family to go to college,” saying comes from.

In the Middlebrow’s own family, one immigrant grandfather became a musician and the other an industrial dry cleaner. Both served in World War II, neither went to college. Both made more inflation-adjusted money than their college-bound children.

But the Middlebrow also remembers both grandparents talking about their hard work to win the opportunity for their children and this notion of higher education as an opportunity won through generations informed my decisions and those of my peers. We were all going to college, it was just a question of where.

Heck, for the Boomer generation of parents, raising a college-bound kid was a sign of success. “You’ll go to college or I’ll kill you,” was a staple of pop-culture comedy. Bill Cosby built routines and episodes of his sitcom around it.

We were steeped in movie comedies from the 1970s through the 1990s that celebrated college not for future earning potential but as “the best years of your life,” where young people would find freedom from the social controls of high school while avoiding the onslaught of adulthood.

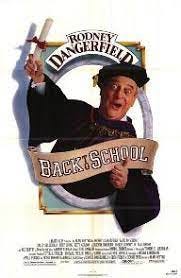

As tuitions have soared and the debt to finance an education has become debilitating to the rest of life, the romantic notions of the university as a place to explore art, sex, literature, alternative lifestyles and chemically-enabled anthropology of the soul all seems a bit risky and irresponsible. The Rodney Dangerfield classic Back to School would make little sense, today. No parent, already successful at business, would pay five to six figures to attend school just to teach his son not to be a drip.

The kids I know who are choosing work over school were raised by parents with degrees, including advanced degrees, and professional certifications. But they are not freaking out over their kids’ choices. They are not speechifying about “the best years of your life,” even though they very much enjoyed their college years.

Anecdote ain’t data and there might be some social benefits to deprioritizing expensive educations as a right of personal and professional passage, but it does seem like some of the mystique of college has worn off. That’s a little sad, and we do need a better and more inclusive way of spreading knowledge of humanities and civilization.