Art and Culture at Poster House

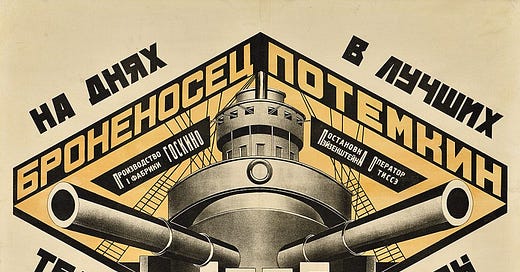

A fantastic display of early Soviet film poster provokes and educates

For any of you in our around New York City before August 21st, The Middlebrow heartily recommends a visit to Poster House on West 23rd street, near the Flat Iron building. Posters are under appreciated as art despite their ubiquity as advertisements and their accessibility to collectors. Poster House gives the medium the full museum treatment. Their curators also write some of the best wall copy around. We attended the exhibit last weekend as part of a block party sponsored by the museum, an outing organized by The Scholar Wife and Renaissance Son.

Among their current exhibitions, “The Utopian Avant Garde: Society Film Posters of the 1920s” is a fantastic history lesson and also a cautionary tale for all artists who seek a voice in how their societies are run and how their cultures function. What happens, one has to ask, if we get our way?

Kurt Vonnegut remarked that he was basically a socialist when it came to his politics and economic preferences but that he was not a Marxist or a Maoist because writers and other creative types fare poorly when those types come to power. In the early years of the Soviet Union there was a creative explosion that you’d expect in a society suddenly freed from royal whims. But Lenin’s project was distinctly Utopian and to achieve it, his government needed too educate and motivate a large and largely illiterate population. Film seemed a good medium for this and image driven posters would drive audiences into the movie houses.

Young Soviet society had no shortage of its own filmmakers and poster designers. Particularly featured by Poster House is the work of Vladimir & Georgii Stenberg, two brothers who had developed a technique for taking stills from films and then turning them into captivating images through alteration. The Poster House exhibit features a lovely short film of the brothers at work, one of the best The Middlebrow has seen as part of an art exhibition.

The idea of art in service of Utopia sounds, well, Utopian, and communist artists in the early years of the Soviet Union embraced the mission. This is what they had wanted, after all. They have overthrown a tyranny and did not expect it to be replaced with another. Decades later, Bertolt Brecht would follow the same path, writing “learning plays” like The Mother that didactically taught the audience about the importance of labor unions and worker control over factories.

For Lenin and more so for Stalin, the point of art was to endorse and spread Soviet values. That meant controlling the subjects of narrative art, especially film. It also meant that foreign films, which might celebrate western decadence and individualism had to be banned. In a way, this banning encouraged local creativity and meant that Soviet film directors could practice their art without having to compete with an infant but powerfully funded Hollywood industry. Even within the confines of the Soviet project, they came up with some creative premises. One lost film described in the exhibition is about a rich man with irritable bowels who buys the appetite of a poor but healthy bus driver. When they trade constitutions, the bus driver becomes miserable and is unable to tolerate food while the rich man turns to gluttonous joy. The idea screams of Gogol or Kafka.

Ultimately, censorship can only end in heartbreak for artists as their Utopian visions clash with those of an unaccountable power structure. This happens in “free” societies, too. When artists get their way culturally, they soon find themselves bound by the rules that society has adopted, often at their behest. In the U.S., we don’t censor artists through the government very often, but we do censor them through corporate actions and by denying them access to the marketplace.

The lesson is that any Utopian vision, if it becomes part of the political or cultural power structure, will turn censorious and restrictive, even if it nurtures bursts of creativity early on. The film poster exhibit on display is a warning, really. But also a lot of fun.