Over the weekend, The Middlebrow headed to City College of New York, an important place in the postwar middlebrow renaissance that powered America’s role in the 20th century, to visit the assembled vendors at the Empire State Rare Book and Print Fair.

On a rainy Sunday, attendance was a bit sparse but the volumes on display were amazing, each with a story to tell beyond the words within the covers. In an era where we have divorced content from form (and I, to be fair, have lauded online sales platforms like BookBub), this is no surprise. Books are heavy, take up space and are frequently given away or sold second hand at huge discounts. The romance of the hard cover and the thick page do seem like a burden when it’s time to move or to clean out an old house. In an age where we demand access to our media from anywhere we might be, at any time, a book that can be accidentally left behind or lost seems quaint.

To their advantage books don’t run out of batteries, refuse to pair with your wireless earbuds or have easily crackable screens. They are also a one and done purchase — there are no further licensing fees. Also, a book doesn’t interrupt your reading with other enticements like an email for work marked “important” or a text from Express offering you $30 off of a $100 purchase even though the stores contain no combination of items that add up to $100.

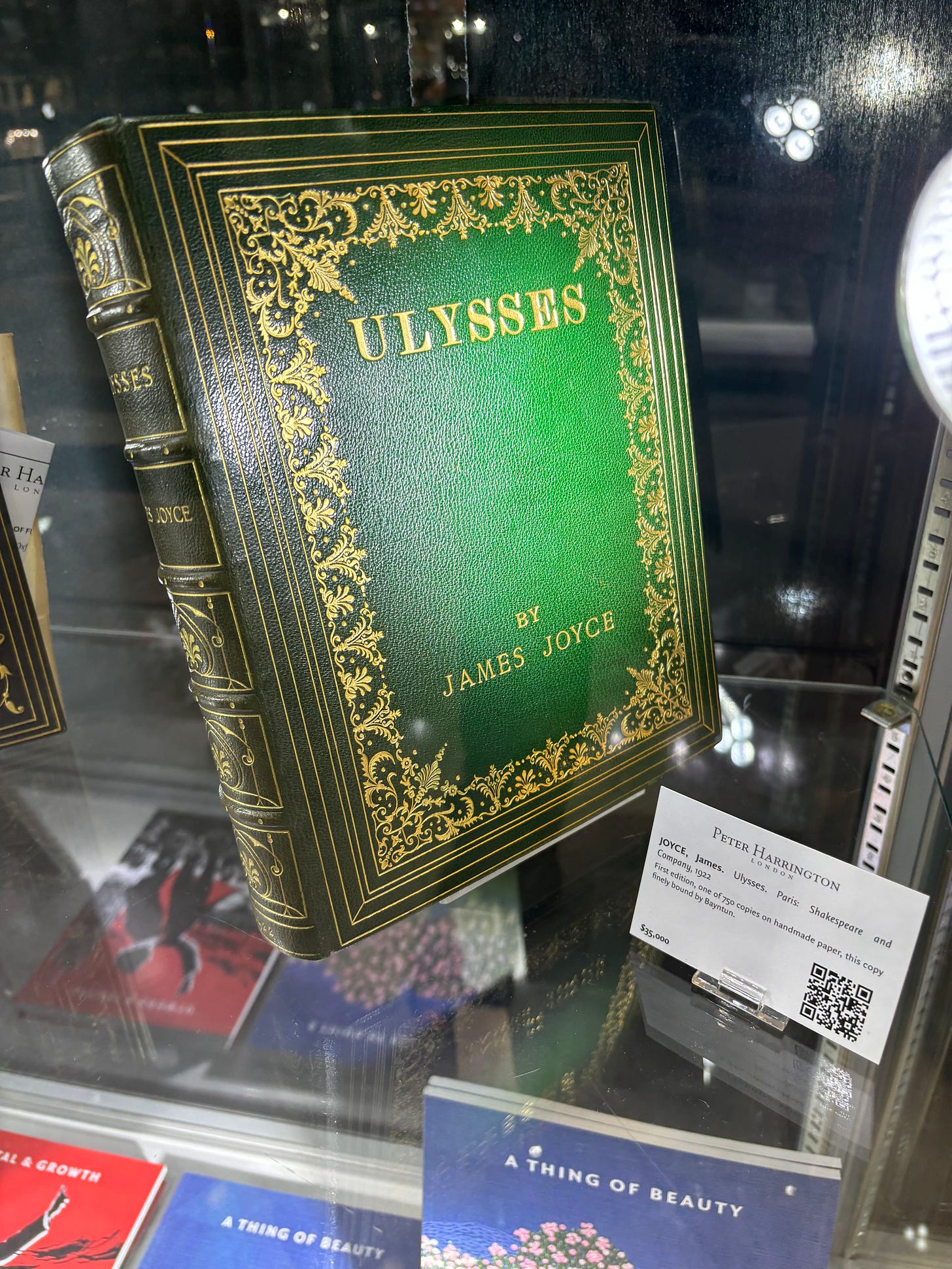

Beyond that, books have stories — they were purchased for reasons, given as gifts and preserved. They are also, in most cases, the medium that the author intended for their work. These stories were on clear display the Peter Harrington Rare Books booth, with a rich collection of literary and jazz history.

Check out this copy of Ulysses with the Victorian-style cover. This is one of 750 printed on handmade paper by Sylvia Beach at the Shakespeare & Co. bookstore in Paris in 1922. The original, pale blue cover is inside. The owner protected a book with a binding by the company Bayntun that mades it look more like something on Dr. Watson’s shelf than the first canonfire of literary modernism.

Speaking of censored literature, here are three novels by Henry Miller, all banned by the United States Postal Service. Tropic of Cancer is even marked as “not to be imported into Great Britain or the U.S.A.” It turns out that the censor who banned these books, Huntington Cairns, was a friend of Miller’s and the author inscribed the 1936 first edition of Black Spring to him.

Elsewhere on the floor, I found a signed photograph that might have inspired Miller quite a bit:

Finally, I’ll leave you with a book by Al Gore and one by Eric Jong, both inscribed to Ruther Bader Ginsburg. The dealer refused to tell me how he got hold of the Supreme Court legend’s library. The truth is probably less interesting than his initial claim that “she was my grandma.”