Unemployment is low now, to the point where some complain of a labor shortage. But among people with degrees in the arts, it’s in double digits. That unemployment number would be higher if you counted people working outside of their preferred creative field. The so-called “creative” corporate professions are full of people who would rather be working on their visions. The market for culture, particularly as it has become more homogenized, leaves ever more people out. But it doesn’t have to be this way and it wasn’t always. The U.S. government once took some responsibility for cultural production, even to the point of creating jobs in the arts.

Last weekend, the Scholar Wife, The Renaissance Son and The Middlebrow visited the National Museum of the American Indian in lower Manhattan. There we saw “Dakota Modern,” an exhibition of masterly paintings by Yanktonai Dakota artist Oscar Howe. First trained at the Santa Fe Indian School studio, he then studied with the government during the Great Depression, where he learned to turn his painterly skills into large murals for public buildings and auditoriums. He then created public works for money in the years leading up to the Second World War. This helped launch a vital career that spanned until his death in 1983.

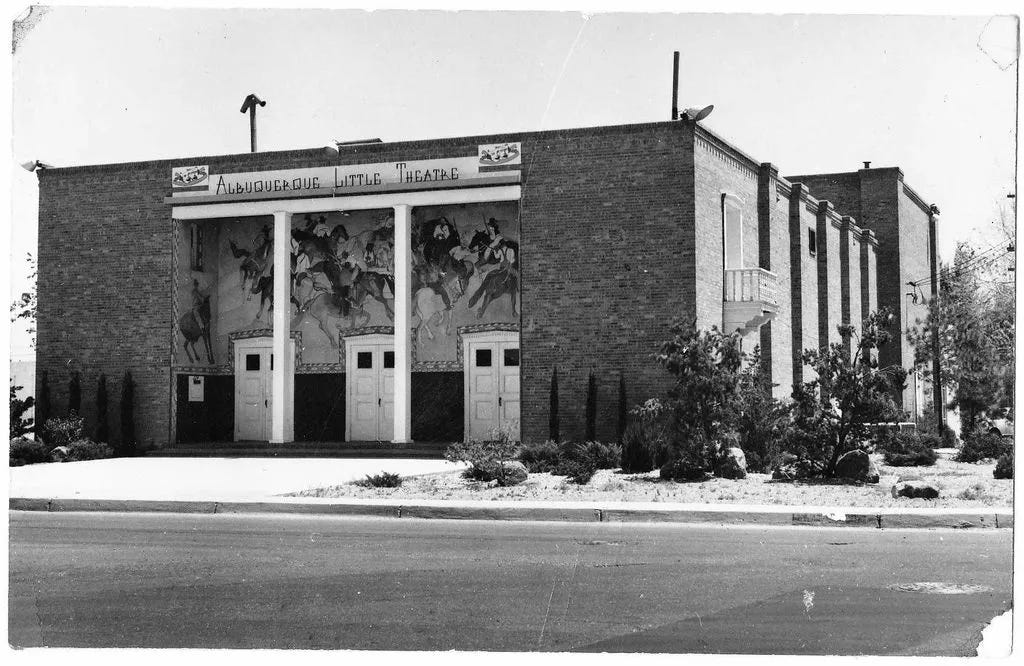

In all, the WPA supported the creation of more than 100,000 paintings, photographs and sculptures. The WPA and the Farm Security Administration supported the creation of the 1941 book 12 Million Black Voices a collection of photographs detailing the black Depression experience, with text by the great Richard Wright. The first WPA building put up in Albuquerque, New Mexico in 1936 was the Albuquerque Little Theatre which is still producing plays as it approaches its centennial.

There are always problems with public arts funding — differing tastes and values among taxpayers chief among them. For that reason, the WPA favored social histories and a civic minded realism. But, if you look to Howe’s paintings, you’ll see that the skills he learned while creating art for the public evolved over time so that his style, always based in his Dakota culture, began to incorporate more experimental and contemporary styles, including abstraction.

Howe so pushed the boundaries with his painting that a festival jury refused to acknowledge his art as Native American. Howe responded with a passionate letter defending the rights of indigenous artists to continues their progress and to engage with the world around them rather than to conform to fixed notions that pinned the Dakota culture to a cork board like a lepidopterist’s butterflies.

Because the arts are an always moving, changing and vital conversation between artist and citizen and citizens and society. The WPA administrators understood this and built things that were lasting and important.

Back when The Middlebrow lived in Albuquerque, the “old chestnut” plays favored by the company in residence at ALT did not appeal. But what mattered was not my entertainment. What mattered is that there’s a big difference between living in a small city that valued having a historic theatre and one that does not.

The WPA not only saved people from starvation in exchange for a little work, but it expanded people’s notions of what was possible. The Middlebrow’s grandfather left Arthur Avenue in the Bronx to build trails in Yosemite. It changed his life.

Once the Depression ended and an entire economy shifted to wartime production and then to wealth (relative to other countries, depleted by World War II), the government never again experimented with massive employment projects using public funding.

For skilled people seeking careers in the arts, a lack of public support in an unforgiving market means that luck plays an enormous role in success, that family wealth and connections play and even larger role and that a majority of hopefuls are pushed away from their callings and towards other work. That work inevitably changes them as it demands ever more from their time and intellect.

We are a rich nation that has left almost all of its cultural production to the whims of the market. Our benign neglect of culture has led to a widespread, boring conformity and a 2020s landscape that might someday be compared to the suburban 1950s. The big movies, the music, the bestselling novels — they all suffer from sameness because we have made no collective effort to find and elevate new voices. Instead, we let most of them scrap for wages and hand cultural power to a small elect from the right schools or the right families (usually both). The major innovations in the visual arts are so far lame. NFTs have virtualized what should be a physical experience and AI visual composers are nothing but fancy scrapers of Pinterest and stock image galleries.

We can do better. During the Great Depression, we did. The quality of Oscar Howe’s work, nurtured at a crucial time by the WPA, convinces utterly.