Wit and Its Relation to the Socially Unconscious

Woody Allen's Zero Gravity and the Changing Face of Comedy

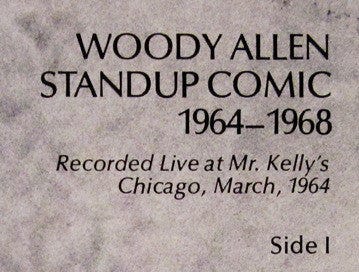

This year, Woody Allen published Zero Gravity, his first collection of comedic stories in 15 years and it’s been since 2013 that he’s contributed humor to The New Yorker. Allen wrote frequently for the magazine from the 1970s through the 2007 publication of Mere Anarchy in 2007. His early stories, collected as Side Effects, Without Feathers, and Getting Even tended to straddle comedic genres – some were expanded bits from his stand-up routines, some read as short stories and others as comedic essays.

My favorites, over the years, included journal entries by the Earl of Sandwich as he experimented with meats and breads and tried to correspond with Voltaire – this was in the style that would influence a lot of online humor like McSweeney’s. Another stand out is “The Kugelmass Episode,” where a humanities professor uses a magic box to enter the works of Flaubert to have an affair with Madame Bovary but eventually finds himself trapped in a Spanish language textbook, stalked by an irregular verb.

Allen’s prose has long evoked comparisons to celebrated New Yorker humorist S.J. Perelman and the new collection is written almost entirely in that style. This book is a throwback to Perelman’s style and might express a nostalgia for a kind of comic prose styling that has grown rare as our reading has moved from periodicals to websites. Written online humor tends towards realistic, observational comedy and political point scoring. Raconteurs on Twitter might think they’re playing on the same field as Oscar Wilde or Dorothy Parker, but most of it tends towards the style of John Oliver where the joke is always like this, delivered in flabbergasted British:

“I sit at a desk and describe for you, with growing agitation and perplexed amazement, a political situation that I and my staff find appalling and that we know with near certainty that you find appalling as well because your entertainment depends largely on our agreement. Now I highlight a politician who we all already dislike and I get a little shouty as I show off what a cynical bastard he is. Finally, I drop an F-bomb, settle back into my seat as if I’ve just won a pivotal round in a Madison Square Garden prizefight, do better, you’re welcome.”

That’s not to knock Oliver, just to say that he’s emblematic of a comedy of rhetoric rather than a comedy of writing and that this style seems dominant online, setting TikTok amusements aside. In Allen’s book, the topical references are scant (reincarnated lobsters attack Bernie Madoff in a third avenue diner and the pansexuality of Allen friend Miley Cyrus is explored) and the stories are written in a comic style that pushes the boundaries of realism.

For example, Allen takes the premise that self-driving cars will have to make ethical decisions like whether to protect the passengers or a gaggle of preschoolers crossing the street and winds up with the story of a Buick “thoroughly grounded in the classics; everything from Plato to Kant, Wittgenstein, you name it.” Our car awakens to its existential freedom while under the ownership of “A.D.H.D Dildarian, the noted physicist who proved that the next Kleenex that pops up when we pull one out of the box is an illusion.”

The tone here is akin to Allen’s early film comedies like Take the Money and Run or Love and Death – the action is in the world but apart from it. Characters have ridiculous names like Grossnose and Butterfat and the tales are filled with sentient animals and reincarnated investors.

Allen stopped making that sort of movie after the 1977 release of Annie Hall and his most fertile filmmaking period in the 1980s was grounded in New York City realism with films like Crimes and Misdemeanors, Hannah & Her Sisters, and Husbands & Wives. While it’s not weird that a director and writer as hardworking as Allen would want to move on to other topics and styles, it is weird that the whole genre of ridiculous comic filmmaking seems to have died out as well.

Mel Brooks is 95 and retired. The 90s and 2000s offered a bunch of silly, reality-pushing movies from the Austin Powers series to Dodgeball, and the antics of Sacha Baron Cohen but we seem to have taken a pause in that kind of comedy, though the superhero blockbusters really deserve a takedown from Zucker Abrams and Zucker. Interestingly, Adam McKay and Will Ferrell, who teamed up on Funny or Die and comedies like Anchorman, have since gone their separate ways and McKay has chosen a semi-serious comedy of social commentary like in The Big Short and Don’t Look Up. Which is fine – but there’s more to comedy than social commentary. Prose and stand-up used to also feature stories about people like Eggs Benedict.

In a lot of Woody Allen’s movies, there’s nostalgia for bygone comedies from Bob Hope, Buster Keaton and the Marx Brothers. Zero Gravity fulfills the desire for screwball prose and stand-up that doesn’t get much of an airing these days. It’s a great summer treat.