Middlebrow watched the first three episodes of Peacemaker over the long weekend. Though not a DC guy, the show amuses, though Scholar Wife and Rennaisance Son are less impressed. The tale of D.C.’s killer vigilante who wants peace in the world so badly that he doesn’t care who he has to kill to get it celebrates 90s-style humor that’s not derided as “Edgecore.” Lots of sex jokes. It’s juvenile.

But, it’s about a guy who thinks he’s a hero who executes his victims for their affronts to world peace. This is D.C.’s version of The Punisher. It’s supposed to be childish and immature. The very notion of it is, to quote The Bloodhound Gang, “not old or new but middle school, sixt grade like junior high.” Except that, judging by the Rennaisance Son, 6th graders don’t act this way anymore.

Also, Hollywood attempts to turn superhero stories into prestige television and Oscar-worthy films, seems to have warped expectations. No matter how complex and adult you try to make these stories, they are adolescents. This is not a bad thing. But it is a true thing that nothing in the multivere of madness can change. It seems that Hollywood’s attempt to turn these comic book stories into enduring and varied universes that can support multiple new movies a year to 2040 and beyond is behind this attempt to fool the culture into believing these are not amusements for children.

While fact-checking at Forbes, which was during the time of Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man movie, Middlebrow asked Marvel’s Avi Arad if we would ever see movies with crossovers between the heroes. The fun of the comic books was always that all the heroes existed in the same world and that sometimes Spider-Man and Wolverine or The Thing and The Hulk would share adventures. Arad told me that this would absolutely never happen in the movies. His strategy at the time was to license the characters individually and to make money, not to build a Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Obviously, those plans evolved. Studios have merged and Disney now owns the intellectual property to almost all 20th century American childhoods and Sony has would rather cooperate with the Mouse than have a Spider-Man who can’t hang out with the Avengers. The MCU is now a multiverse. If Sony and Disney can share toys, why not Warner Brothers and Disney? Captain America and Batman can fight Mr. Smith in the Matrix.

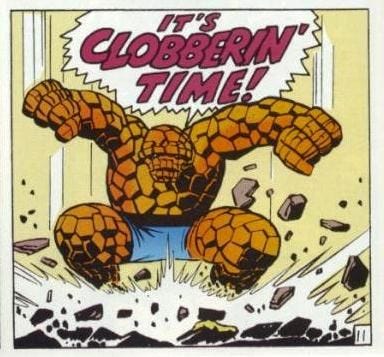

When I grew up reading comic books, an advantage of the medium was that its artists could render scenes that it would be too expensive, or impossible, to do well in movies. Stories needed no unity of setting or even time. Scenes could take place in the hearts of exploding stars. Heck, it wasn’t until Raimi’s Spider-Man that anyone was able to render web swinging and goblin gliding in a way that wouldn’t look cheap and phony. A character like Iron Man, encased in armor that moved like flesh in the comics, seemed like too much to ask. We not only got that in 2008, but the character turned out to be the protagonist of the first wave of super hero movies. Somehow, despite all of the CGI advances, nobody ever produced a decent looking version of the rock-covered Thing, though.

The generation of Marvel movies that began with 2008’s Iron Man accomplished in films what a young Middlebrow comic book reader assumed impossible. In that sense, these movies have been fan service for byone childhood. Because, no matter how sophisticated a writer makes a superhero comic, they are for kids. Even the “adult” stuff like Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, which holds up well to adult rereading, is best first consumed in high school. Comics are children’s literature, sometimes vitally so.

But these days, about half the comic book audience are adults (mostly men) and the older consumers really dominate sales from comic book specialty shops. There’s nothing wrong with enjoying childhood memories, of course. But comics are for kids and so are the movies inspired by comics, even if they have adult elements that attempt to make them enjoyable for as adult audience wanting to bring their kids to a movie.

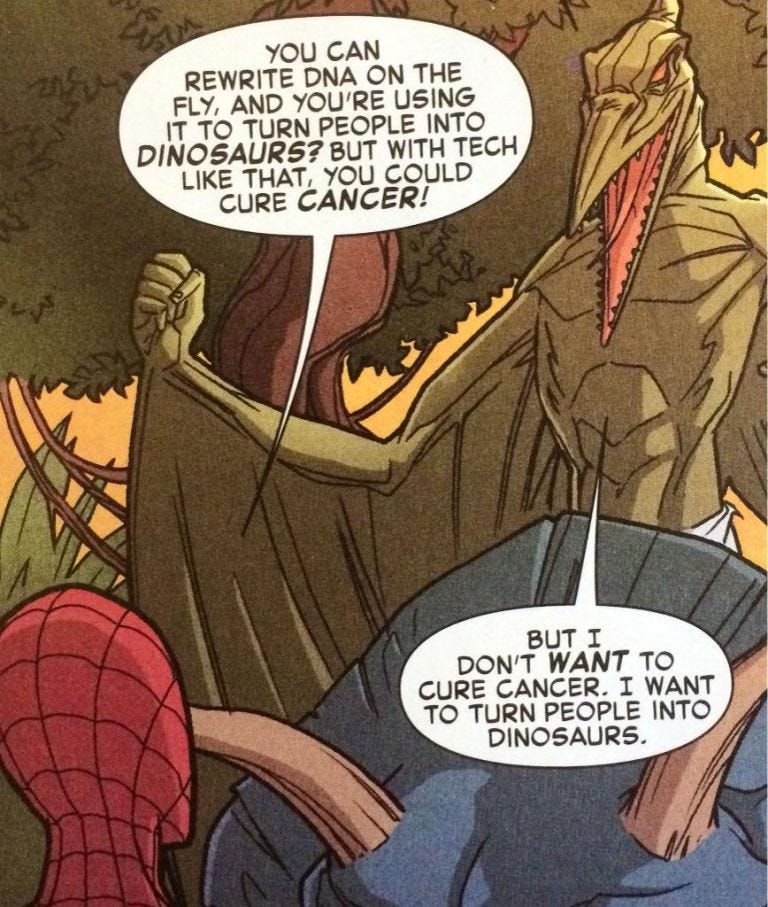

You can tell these movies are for kids based on how many of the problems are solved by punching. These people all have fantastic technology and abilities that they use almost solely for mayhem (and that’s the good guys).

This, aside from general crankiness, is why Alan Moore, creator of The Watchmen, which exposed super hero comics as hiding fascist themes, wants nothing to do with Marvel or DC’s super hero movies.

Super hero movies wouldn’t have been culturally worth worrying about 20-30 years ago, when art house movie theaters still existed and small budget, independent films could still find audiences. These days, they seem to be sucking all of the cultural air from the theaters. The new Sipder-Man movie has been the top U.S. box office draw since its mid-December 2021 release. It’s not even close. It’s the only movie out there that can draw people to theaters (during admittedly extraordinary times).

When Martin Scorcese complains that Marvel movies aren’t cinema and that for all their fun and spectacle they lack the human elements of storytelling that adults need and should crave, we should listen. The problem is not that there’s anything inherently wrong with childish amusements (even for adults). The problem is the dominant role they play in our entertainment. Middlebrow doesn’t love analogies of culture to diet. A Marvel movie isn’t apple pie to the leafy greens of reading James Joyce. But roller coasters and water slides are also childish amusement that adults enjoy. It would be a problem if we only took our pleasures that way and never played a game of tennis or chess for fun.

We need more diverse amusements that are not all anchored to our adolescent memories. At this point, if you take all of the Marvel and DC movies and TV shows and then all of the movies and shows that are functionally like them (problems solved by punching) there just isn’t much left. That’s sad.