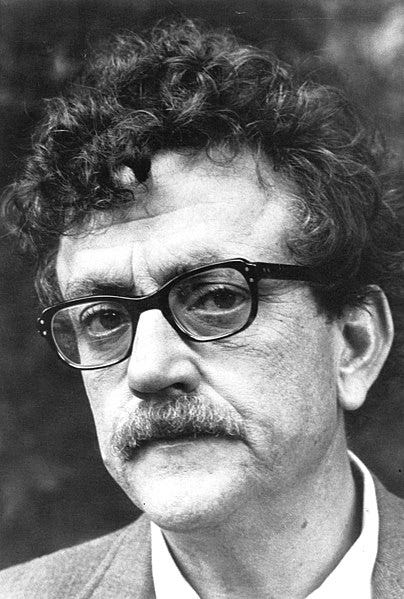

Getting Unstuck with Kurt Vonnegut

Why so many multiverses?

With Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time, director Bob Weide finishes a project forty years in the making, detailing the life and work Vonnegut as author, artist, family man and public intellectual while also retracting his friendship with arguably one of America’s very best authors, to be ranked alongside Philip Roth, John Updike and Saul Bellow.

What stuck with me most was how at the start of the film we are told that Vonnegut felt that he was unstuck in time, the same way that Billy Pilgrim, the soldier-hero of Slaughterhouse-Five bounced from moment to moment in his life. Vonnegut saw the firebombing of Dresden, Germany, during World War II, the atrocity that inspired his novel before it happened, he insisted, while in a forest with his forehead pressed against a tree. Linear time might be nature’s most persuasive illusion.

The MIddlebrow has noticed lately some complaints about the current trend in Hollywood towards movies about multiverses. Marvel paved the way, first with the latest Spider-Man installment and now with Dr. Strange. Both Marvel and D.C. comics have long relied on alternate universes for their storytelling (as has Star Trek in its many incarnations). The idea of alternate universes can free creators from the certainties of narrative decision making. It unmakes the old Greek way of telling stories. Imagine the play Oedipus and the Multiverse of Madness where, reacting in different ways to the prophecy that he will kill his father and marry his mother, he lives a live of celibate peace. Are there universes where Oedipus dodges his fate? Or would fate thwart him in every dimension?

In Slaughterhouse-Five, the aliens from Trafalmador urge Pilgrim not to ponder such questions -- time and dimensions and alternate realities are all beside the point. We are like insects in amber. Our condition matters in the moment. Enjoy the good moment, the aliens tell Pilgrim. Try to ignore the bad.

It may be that in 2022 we are collectively wondering if we might not have made some better choices leading up to this moment. No reason to belabor the last few years, but one imagines that Vonnegut would have been outraged by them.

Vonnegut described his work as persuading his audiences to embrace impossible premises: A man is revealed to be an automaton. A man jumps around through time and space, seemingly at random. Time stops, reverses itself for a decade, and forces everybody to relive 10 years of their lives. The President of the United States in a post-apocalyptic world persuades everybody to become members of random, extended families. Humans stranded on Galapagos evolve into a new species. Ice-9 freezes the world. These are the ones I remember most quickly.

These implausible details, along with the marketing of his early books, led some to classify Vonnegut as a science fiction writer, rather than literary writer. In a world that’s given us George Orwell, Ray Bradbury and Neil Gaiman, there should be no opprobrium in that. But literature is its own genre with its rules and biases, and for Vonnegut this classification did translate into some measure of disrespect and even lost earnings.

The popularity of Slaughterhouse-Five and Breakfast of Champions, not to mention the profundity of each, made Vonnegut an undeniable literary and cultural force. But Weide’s documentary shows how quickly the influential New York Times Book Review turned on the author, accusing him of relying on old tropes and outright trickery from the1980s through the publication of his last novel Timequake, in 2001.

What The Times had done, and many followed its lead, was to turn against the middlebrow sensibility that made Vonnegut great. When Vonnegut taught creative writing in Iowa he told his students to go ahead and strive for importance, but to be entertaining along the way.

In all his books, Vonnegut grapples with philosophical, religious and social questions. But they are not hidden. If T.S. Eliot makes a classical literary allusion in his writing, the reader has to know it to find it or to know enough to read the text hermeneutically and to tease out all that’s there. Vonnegut, trained first as a journalist and then as a public relations hand, hides nothing. If he references Plato he tells you so, what the reference is and why he made it. Both approaches have merit. It is rewarding to bring prior knowledge to reading complex texts and then to see how those ideas are incorporated, sometimes very subtly. But there’s also value in having a mind like Vonnegut’s say, “Look, here’s what you need to know about Darwin and evolution for the purposes of reading this story and if you’d like to study further, let this book be your starting point!’

As a commentator in Weide’s documentary put it, The Times couldn’t imagine that a book that can be understood by a high school junior could be all that important. How strange, since we read all of the American Jazz Age writers and Shakespeare in those years. If those writers are not important, who is?

The writer The Middlebrow thinks of first as influential, important, dense and difficult in the 1970s would be Thomas Pynchon. But the line between Vonnegut and Pynchon isn’t that far. There’s more conspiracy in Pynchon and he often does larger, more sprawling tales, but the reader of one would seem likely to enjoy the work of the other.

It was pure snobbery that kept the supposedly learned critics of The Times from placing Vonnegut among his peers. Vonnegut trafficked in many of the ideas, like multiverses and parallel universes, that seem in vogue now, though they are old as myth. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a multiverse tale, after all, as is Flatland. We probably need to know that our lives can be different, if we’re going to keep on. Sometimes it seems so unlikely that we need fabulists like Vonnegut to convince us.

So it goes.