How To Revive Intellectualism in the U.S.

Everybody is a scholar, whether they know it or not.

At Castalia, Sam Kahn recently published an essay called “How The Intellectuals Lost (Many Times Over)”, mourning the death of what he calls “high culture.” It’s worth a read and this Middlebrow is a reaction to it. First, let’s quote Kahn at length:

I recommend the entire essay, as Kahn traces the ups and downs of intellectualism in the West from the Enlightenment onwards, but this is of particular relevance to The Middlebrow:

“If, in the 19th century, part of being a ‘gentleman’ required having a certain degree of educational attainment, participation in an elite class in the mid-20th century similarly required at least a passing familiarity with ‘high culture.’ You were sort of supposed to have read the ‘great books’ in school, prior to thoroughly forgetting them, and to least look at arts sections of newspapers before flipping back to sports. It’s very interesting to watch, say, early Woody Allen movies and to see how deeply affected he was by the reigning high culture. Great educational uplift projects — Leonard Bernstein’s classical music lectures, Mortimer Adler’s Great Books collections, etc — were based on the assumption that a rising middle class would necessarily need to familiarize itself with high culture. This was the premise that the leading writers of the era, Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Tom Wolfe, etc, toyed with and satirized throughout their careers. The idea was so baked in to the culture that Bourdieu developed a sort of pseudo-science out of it with his theories of cultural capital.

But, as it turned out, cultural capital was largely built on a house of cards. What David Brooks was describing with the ‘bobo’ was the easy peeling away of the underlying premise of ‘cultural capital’ in the last decades of the century. There just was no need to read a lot, or use a lot of fancy terms. Cultural attainments didn’t help you mark out status as part of a Bourdieuian cultural elite; they just made you weird and pretentious. Better, instead, to watch the same TV shows as everybody else and listen to the same music as everybody else and advance your social capital simply by having more money.”

At some point, we just sold off the importance of appreciating European film, opera or challenging theater. We adults gave up on the idea of being able to respond to the visual arts with some knowledge and insight beyond “my six year old cousin could draw that.” As we made that trade, we stopped expecting or even wanting our kids to learn appreciation skills in school, in favor of job training. This might be why, by the way, that so much of what passes for social studies these days is similar to the diversity, equity and inclusion programs that are part of the Human Resources programs at major corporations. While the benefits of diversity and inclusivity can be taught through subjects like ethics, epistemology and aesthetics. The lessons of To Kill a Mockingbird, Heart of Darkness, The Invisible Man, The Beautiful Struggle and Orlando are in the books — assigning them and helping young people to understand them changes people for the better.

The attainment of culture and literacy isn’t just about status, contra Brooks, it’s about becoming civilized and learning to live together. It’s about art and philosophy inspiring people to improve themselves. The corporate HR model ultimately leaves people’s inner lives unchanged, using the cudgel of wages to encourage repression, but not the revision, of harmful ideas.

Kahn chalks this up to society’s adoption of the language of mass marketing, and this probably represents a deeper economic force where, in an age of scarcity and competition, a “good enough” standard emerges where people accept and pay for goods and services that they don’t particularly like and still think of themselves as free agents, exercising choice. In a society of truly free consumers, nobody would tolerate the inconveniences, discomforts and indignities of coach air travel. People would rebel over everything from cramped seats and delays to being overcharged for snacks and water by concessionaires who can price gouge because they are within a security zone that insulates them from competition. But airlines and airport vendors, in informal collusion with the government, know that their customers lack choice and will accept most anything to get to their destinations.

The airline “good enough” shuffle is repeated throughout the economy and it serves to both lower expectations and to motivate people to seek money, rather than culture, as a primary goal, because the only way out of the “good enough” economy is to buy your way out.

It is fashionable, in this age of corporations claiming to care about the Environment, Society and Governance, for companies to claim to have “values.” But corporations cannot really have values that transcend the obligation to create profit for shareholders. That doesn't mean they are doomed to evil, just that their values will always fit into the framework of profit generation for owners, if not on a short timeframe, then a long one. Always. The profit motive is the gravity that holds a corporation together, no matter what its managers claim. This is why a corporation can radically change its actions, like Ford devoting massive R&D spending to electric vehicle production one year and cutting the program the next, while claiming its values are intact. Or, consider GM actually suing the government in opposition to environmental regulations while accepting federal bailout money during the financial crisis and admitting no hypocrisy at all.

If you don't want to accept the Milton Friedmanesque argument that companies follow the profit imperative before all other values, consider that even the alternative "multi-stakeholder" approach preferred by adherents of ESG will fail to produce a corporation that can have coherent values beyond vague platitudes. The multi-stakeholder approach says that companies serve their customers, shareholders, employees and society, in roughly that order. But these groups not only have competing interests with each other, but are so internally diverse that no company of size can take an immutable ethical stance without serious risk. Just ask Anheuser-Busch InBev, which managed to alienate one segment of his customers with an ad campaign celebrating a nonbinary celebrity and then alienated the rest by backtracking after the backlash negatively affected sales — hardly a profile in courage, but it's naive to expect better from other companies who will all ultimately cave when financial results are threatened.

Ultimately, the “good enough” economy is nihilism, propped up by its backers as Econ 101. Another way to think about it is as Panglossianism — the insistence that the market economy and competition for money, for all of its degradations, is the “best of all possible worlds.”

The only way to change that without trying to overthrow the capitalist system for something more overtly repressive is to follow the “render unto Caesar” approach and to pursue values that the market cannot price efficiently. That means to devote our time to the study of literature, art, aesthetics and philosophy despite the lacking 1:1 correlation between gaining such knowledge and earning money. This is a fight worth having now as generative AI is the ultimate “good enough” tool that threatens to completely degrade human ingenuity and to destroy what’s left of good taste along the way.

To save our culture, we have to free the arts and humanities from the tyranny of expert specialists who have entrenched themselves within academia, turning works of art meant for everybody into Babel. What we lost with the dissolution of the old “Book of the Month Club” era was the widespread joy of reading. Albert Camus did not write for professors but for people who might make a difference in their own lives and communities. Franz Kafka wrote for all of us since we are all, as Woody Allen remarked in Love and Death, ultimately condemned for a crime we never committed.

There are a few potential answers here. The first lies with the artists, who have to find ways of reaching people in ways that matter. My friends at New Pop Lit believe that some of the answer lies in naturalist writers like Erskine Caldwell, who wrote true and gutting prose about southern poverty. I would add Nelson Algren, a favorite of both Ernest Hemingway and Simone de Beauvoir. For my part, I prefer a more absurdist, surrealist approach that might hit less with its accuracy but exposes our ridiculous circumstances. Something like the new sincerity of David Foster Wallace might bridge the two.

Another lies with schools and teaching. The ability to appreciate art should be considered a value and an essential one to any attempt at achieving social justice. Our mistake has been to dismiss art as frivolity and an obstacle to solving more serious issues. For example, New York City should not destroy the Elizabeth Street Garden and its sculptures (pictured above), to build a housing development while there are other sites, including empty warehouses and office buildings, available. We need to raise a generation that views people with aesthetics and technocrats at least as equals.

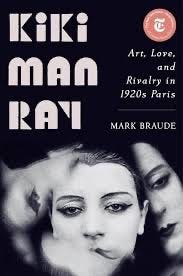

Re-embracing localism might also help. We have no problems buying local when it comes to groceries and will often pay up for near-sourced meats, produce and honey. What about the arts? Another problem with mass communication and advertising language is that it reduces local differences -- just look at the disappearance of regional accents throughout North America and Europe as the non-regional diction of television has spread. Almost everything is national or global now. Local news and entertainments are dying out as people in large and small communities stream the same movies and shows while choosing from the same consumer goods offered by Amazon. In a global market, individuals have very small voices. In local markets, their engagement with news, art and culture matters more. Nurturing more local cultural events, then, might make intellectualism more important in daily life, improving mind and spirit along the way. The fabulous Kiki de Montparnasse is globally known now, but was a decidedly local celebrity in her time, making great contributions to the arts as a singer, actor, and model.

Finally, we all need to talk more about art, literature and music that challenges us and asks us to grow. We have to make it relevant in our daily conversations and we should never fear being seen as pompous or elitist. Nobody was ever shy about deadening our culture, so nobody should apologize for trying to revive it, either.

Thanks for the mention of New Pop Lit!