Leopoldstadt: A New Masterpiece from the Master

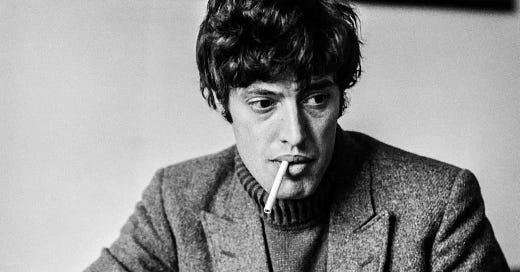

Might Tom Stoppard be the world's greatest English language playwright?

Some of Tom Stoppard I have only read, some I have only seen on film, and some I have only seen live. I wish I’d seen Coast of Utopia in marathon, though the three plays do read almost like a novel. I’ve only seen the excellent film version of Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, though have read the script a few times. I have only seen Rock’n’Roll, and probably need to read it.

The Middlebrow does know this — over time, I like and respect Tom Stoppard more and more, from his youthful outings to his latest works. He is now 85 and some say that Leopoldstadt, now on Broadway, might be his last play. Such speculation seems dangerous. Who knows what’s on his hard drive? Besides, when I stop to look up whether the bard is healthy or not, I find this quotable quotation, “A healthy attitude is contagious, but don’t wait to catch it from others. Be a carrier.” So, I’ll choose to believe that Tom has a lot of life and work let in him.

If we’re going to let people be President of the United States well into their 80s, we can certainly have them writing wonderful plays, right? Leopoldstadt is a wonderful play. It’s not a “late career” play except that its breadth and form would be difficult for a younger writer to accomplish — sometimes it takes years of living to earn the sense of scale for a tale that spans generations.

The play takes its name from the Jewish quarter of Vienna. The story begins in 1899 and we meet a family at Christmas and through their conversation, the stage is set for the Jews of early 20th century Europe. These are smart but real (and realistic) people and the play follows their lineage over the decades, finally ending in the 1950s. Only three survive the Holocaust but that any do, that there is a family legacy at the of end the play, is because of Hermann. Decades prior, when he finds out his wife has had an affair with a gentile cavalry officer named Fritz, Hermann cleverly has the paternity of his son Jacob pinned to the non-Jew. Then, when Hermann transfers the family business to his son, it is not expropriated by the Nazis, as he would be legally recorded a gentile.

The scope is epic. The affair takes place in 1900, soon before Jacob is born. Jacob fights in the first World War and takes possession of the family business in the 1940s. the effects of that maneuver are not realized until the late 1930s and by the middle 1950s, the youngest member of the clan, raised in England, has no memory at all of being a Jewish boy in Vienna. From his vantage as an older playwright, Stoppard seems to be cautioning us that our lives are full of powerful, formative moments that we can’t even recall. That’s a tough insight for a young writer to find.

It’s also tough, stylistically, to tell a tale in five long scenes over five different decades with often different characters while still preserving a sense of suspense and narrative unity. The story is a somewhat veiled telling of Stoppard’s own family tale, though transposed from his Czech homeland to Vienna to create a sense of distance and make it seem less a memory drama.

Amazingly, The Scholar Wife and I, on a Saturday night when The Renaissance Son was invited to a surprise sleepover, were able to walk right up to the box office to purchase tickets.

Every now and then, a show that should sell out every night won't. That is to the advantage of all of us who cannot necessarily plan ahead. If you’re in New York City and find yourself with an unstructured evening, I very much recommend that you jump on this opportunity. There’s not much like it on stage or in the world.

Sorry to say, but I agree with Jason Zinoman's recent assessment in the NYTimes: "As with Spielberg’s movie, the new play by Tom Stoppard, “Leopoldstadt,” is being described as his most personal as well as a reckoning with his Jewish identity, which in his case he didn’t understand until middle age. It’s also one of his worst plays: intellectually thin, overly familiar, blandly generic. If the way you tell the audience it’s the 1920s is by a woman dancing the Charleston, you’ve become too comfortable with cliché. And yet, this sprawling portrait of a half century in the life of a Jewish family from Vienna is drawing sold-out crowds of weeping audiences." Though I don't think anyone was weeping at the performance I went to. Also question why Stoppard didn't set this confessional play against the his own Czech background. Was it just to go with Freud and Schnitzler rather than Kafka and Werfel? The destruction of Czech Jewry is no less tragic and compelling than what went on in Austria. Disappointed because I was really looking forward to seeing Leopoldstadt.