Nesting Dolls of Art with Man Ray

My growing obsessions with the Dadaist, Surrealist and endless inventive artist.

Raised in Williamsburg, New York to a family of tailors, Emmanuel Radnitzky, to become ubiquitous under the name Man Ray (which he took not as a nomme de guerre but as a way to avoid prejudice). He really found his voice when he befriended Marcel Duchamp and moved to Paris in 1921.

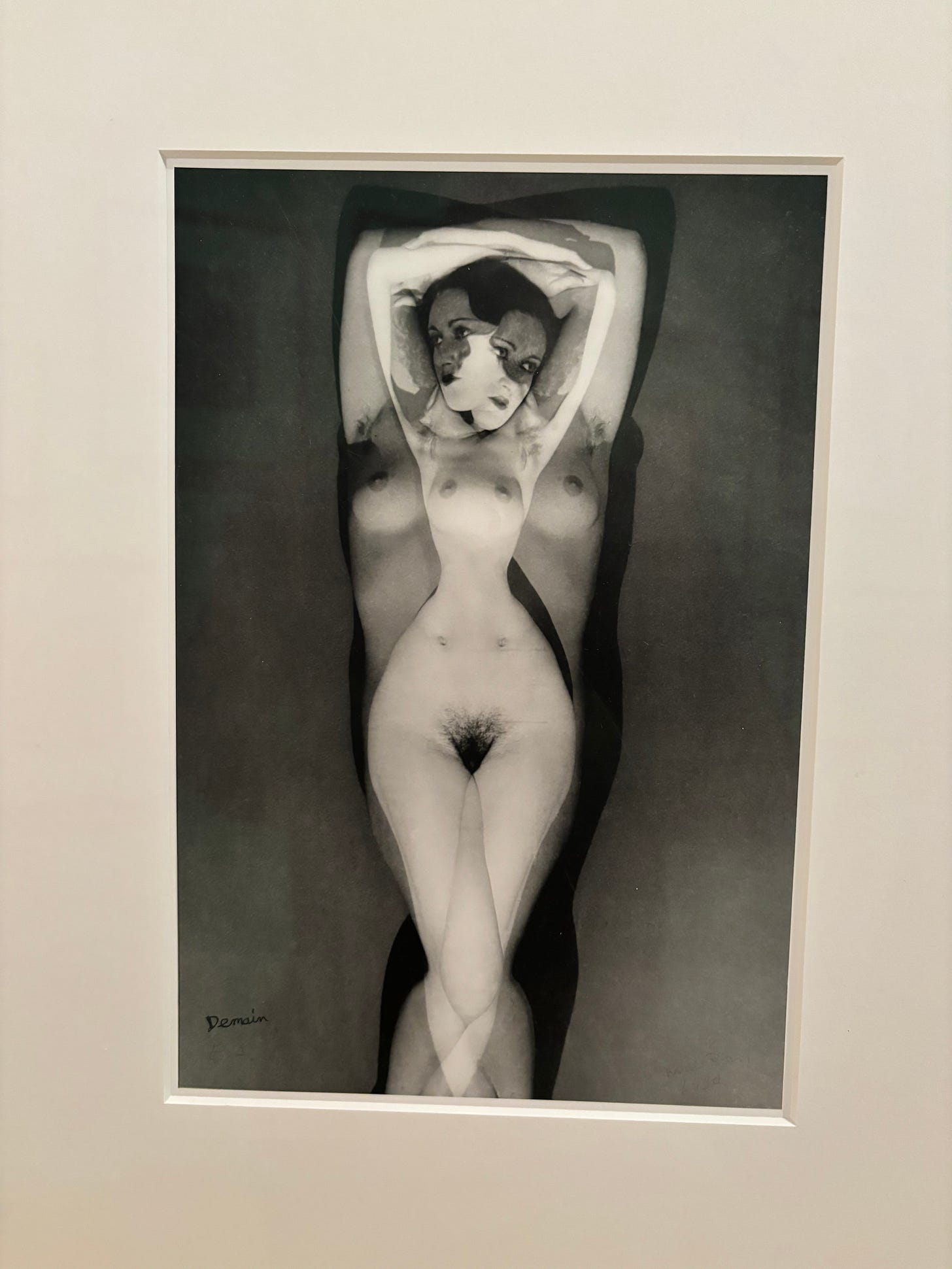

Trained like so many of his time to emulate the Old Masters, Man Ray transitioned from painting to photography and filmmaking. While the photographers favored by Alfred Stieglitz in New York saw the medium as a tool for representing reality with precision, Man Ray brought a painter’s sensibility to the craft, seeing it as a way to interpret reality by altering what our eyes perceive to give us glimpses of deeper truths. He also had an eye for the beauty in people, finding the smoldering in subjects as diverse as authors like James Joyce and Gertrude Stein or one of his muses, the cabaret icon Kiki de Montparnasse.

I first encountered Man Ray in the 1990s, just after college, when I was the arts editor of an alternative news weekly in New Mexico. Site Santa Fe sent me a disk of Man Ray animations — they were motile geometries and it felt like watching an early film adaptation of Edwin Abbott’s Flatland. I remember being charmed and lightly hooked. My exposure to surrealism was through theatre, rather than visual arts. I didn’t understand at the time how deeply it was all intertwined.

Nor did I understand that Dadaism and surrealism weren’t as outside of mainstream society as I had assumed. Sure, I had heard about the connection between cubism and military camouflage and about how the Central Intelligence Agency promoted modernism around the world at the start of the Cold War, but the connections run deeper. Like Ernest Hemingway’s short stories, Man Ray’s photographs permeated mass market magazines like Vogue and surrealists like Ray and Salvador Dalí made massive contributions to mass fashion.

World War I taught us we had the power to destroy civilization and the lesson of World War II was that we could destroy all human life. In the aftermath, we figured out that we could wreck the entire planet, at least for ourselves. We still haven’t figured out how to pulverize our blue marble, but give us time.

The anti-artistry of Dada and the engaged fine artistry of surrealism and futurism not only reacted to the combination of our collective terrible power and flawed judgment, but took society along for the ride, bringing existentialism to the Middlebrow world. It took me a long time to understand this, but artistic, literary and theatrical absurdism has been fully integrated into western culture, from the aesthetics of absurdist theatre defining television sketch comedy to reality television, cooking competition shows and Anderson Cooper as a serious newsperson. We live with the absurd daily and no longer fully recognize its weirdness. This all started more than a century ago.

At the Photo Elysée in Lausanne, Switzerland, there is a private Man Ray collection on display, called “liberating photography.” The portraits above are included, along with hundreds of other compositions, including pictures of the Paris community of modernist writers and artists who formed a community in Montparnasse in between the wars. What really shines in the exhibit is the sense of community among the artists, writers, musicians, actors and models who made up the community. They were all working together to pierce a veil of normal perception that just could not make sense of the emergent 20th century.

Along the way, Man Ray collaborated with Duchamp, Antonin Artaud, Max Ernst and other surrealists. He also photographed their art and turned it into his own, which is where the nesting doll concept comes in — a Man Ray photo of a Duchamp sculpture is art within art, which is deeply rich and humbling. So, I’ll leave you with one of those images, without further commentary: