A political discussion turned literary as a friend and I tried to list older characters in modern and contemporary fiction who are heroes rather than buffoons. Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea, of course comes to mind. Fishing in the oceans off of Cuba, he battles an indifferent nation with unmatched strength, skill and courage. Of course, he fails, but a younger man would have, too.

Sophocles gives us Oedipus in his dotage. Oedipus, blind and cursed and a burden to his children, wanders into the lands of the Furies, who are empowered to torture mortals who have spilled family blood. He is redeemed, somewhat, with the help of the hero Theseus, but the play Oedipus at Colonus is the character’s final act (and the last written by Sophocles as well).

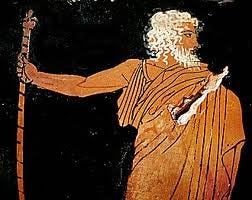

Another character mentioned was Nestor, a supporting player in both The Iliad and The Odyssey. Nestor is often dismissed as an old blowhard, telling fanciful stories of adventures long-forgotten and offering people advice that’s often accepted but generally best ignored. I’m not sure old Nestor is such a Polonius, though. He’s canny, he’s a survivor, and he flows through the old Greek stories.

Nestor is one of the Argonauts, a group of Greek warriors who follow Jason on his quest for the Golden Fleece and who later wage war against the Centaurs. Nestor is a survivor of battles and adventures that are quite unlike what we see in The Iliad which though it has its magical elements, is still a gritty war story. Put another way, to be killed in The Iliad you’ll very often have a spear thrown into your neck, your head bashed with a heavy boulder or your limbs hacked off with a bronze sword. Nestor has seen fire breathing bulls and warriors with human torsos on horse bodies.

Ironically, to get home, the clever hero Odysseus will have to contend with a world more like Nestor’s, full of sea monsters, witches, besotting nymphs, underworld journeys and a man-eating cyclops. But the two meet on the plains of Troy.

By the time of the Trojan War, Nestor is the King of Pylos, and one who has pledged to help Menelaus win Helen’s return after she is taken by the Trojan prince Paris. This arrangement was all Odysseus’ idea. Always looking for an angle, Odysseus arranges that the more powerful Menelaus gets to marry Helen, a daughter of Zeus and the human embodiment of beauty while Odysseus marries Helen’s cousin Penelope, who is also extremely desirable but less likely to be abducted and Agamemnon marries Helen’s sister Clytemnestra, who is also a stunner.

Odysseus has it all worked out, though he doesn’t expect that Aphrodite will grant Helen to Paris, either empowering Paris to take her or inspiring Helen to go with him. It is the pact that Odysseus negotiated between all of the suitors that turns this act of rape, love or something in between, into the cause of what would have been considered a world war.

A figure of legend, Nestor is the oldest king in the Greek armada. The Greeks rely on him for his soldiers and his wisdom, but he is too physically weak to fight. He remains brave, though, and takes to the battlefield in his chariot. If he cannot fight, he can at least lead his men from alongside and expose himself to the dangers they face.

This happens in Book 8 of The Iliad, during one of the more furious battles where the Trojan hero Hector, second only to Achilles in pure killing power, enters the battle to try to drive the invading Greeks into retreat. Paris, not much on the battlefield but good at a distance with a bow and arrow, kills one of three horses pulling Nestor’s chariot. The old man leaps from the vehicle, sword in hand, to cut the reigns tying his chariot to the dead horse as his other two horses panic.

On his feet, vulnerable, Nestor turns to see Hector charging towards him. Diomedes, one of the most respect Greek warriors, “the master of the war cry,” sees Nestor’s predicament and calls to Odysseus for help. And, this happens:

“Stubborn Odysseus refused to listen.

Instead, he dashed back to the hollow ships.”

That’s right, Odysseus runs for it. Diomedes, fortunately, has a chariot pulled by horses that he had stolen from the Trojans. They are fast, fierce and young. So Diomedes fights his way to Nestor and tells the old man to drive the chariot, to wheel around to face Hector. Diomedes tries to fight Hector. It goes badly. Nestor has to convince Diomedes to retreat. Taking Nestor’s advice saves his life, but it gives Hector a run at the Greek encampment, nearly dooming them all.

In earlier readings, I hadn’t noticed Odysseus abandoning Nestor to certain death. Emily Wilson’s sharp, modern translation illuminates a lot. She does not call Odysseus a coward. She calls him “stubborn.” True to his character, Odysseus had made a calculation and he stuck with it. Old Nestor’s life was not worth the strategic risk. Odysseus went back to preserve his army and to defend the Greek encampment. Pylos could find a new, younger king some other time.

Diomedes, Odysseus and Nestor are all among the surviving victors of the war. Nestor loots some treasure but doesn't linger long. Of the Greek Kings, he seems to have the easiest journey home and the least drama afterwards. He holds court in Pylos and Odysseus’ son Telemachus visits to gather information when he sets out on a quest to find his father. Telemachus is in for a lot of talking.

Odysseus, meanwhile, has a terrible journey home. He is plunged into a a mythic world of gods and monsters. Every sailor with him dies. Odysseus goes to the underworld to consult with the shades of Greek heroes and sees the ghastliness of death firsthand. When he finally does return to Ithaca, he is washed up naked on the shore, like a newborn, and nobody even knows who he is. He restores his kingdom, family and honor by the end, but to get there has to go through the supernatural adventure that Nestor went through in his youth.

I wonder if Odysseus betrayal had anything to do with that. Plenty of coincidences in the Greek stories have their reasons behind them, after all.