Last week The Scholar Wife took me to The European Fine Art Foundation’s fair at the New York Armory, where we delighted in mythic works by surrealist, modernist and contemporary artists. She captures the spirit of this year’s fair better than I ever could, and I highly recommend you read her account.

We were both drawn to a large canvas by Salvador Dalí, presented by New York’s Di Donna gallery. It’s a later work, from 1976 and in it, the artist revisits themes from throughout his career, almost as if trying to sum up a world of raucous genius in a single painting. As The Scholar Wife describes:

“As we peer down the canvas, we encounter precious stones and rocks laid in a deliberate pattern at the tree base, a reminiscence of the exquisite and uncanny collection of 39 pieces of fine jewelry Dalí created between 1941 and 1970 as a tribute to his wife, collaborator, and muse Gala Dalí, who shared authorship of many artworks. In the context of this painting chronicling so many decades of the artist’s oeuvre, we also travel back to The Eye of Time, an eye-shaped brooch with a tiny watch face in the iris. The platinum, diamond, ruby, and blue enamel treasure with a mechanical Movado watch movement, was crafted by Argentina-born jeweler Carlos Alemany, who ran a workshop in the St. Regis Hotel in New York. Viewing the composition as a whole, we recall shapes, colors, and compositions of earlier works Persistence of Memory (1931) and Diurnal Fantasies (1932).”

Now, maybe you see Dalí mentioned here and you’re rolling your eyes a bit, because the name does bring up images of melting clocks on posters, tacked to the wall of a college dorm room. For all his greatness, there’s something about Dalí that became so iconic and commercialized that he can seem trivial, if always fun. Related, you could imagine having a conversation like this, if you went to college in the 1990s:

“Then we went back to that girl’s room.”

“Which girl’s room?”

“The one with the poster of Gustave Klimt’s ‘The Kiss’ on the wall.”

“Right, which girl?”

I digress, but not far. I spied on my bookshelf a thin Dover publication that I’ve been carrying around for years but realized I had only flipped through for its line drawings, called Dalí on Modern Art: The Cuckolds of Antiquated Modern Art. It’s a reprint from a book Dalí published with The Dial Press of New York in 1957. The Dial was a massively important modernist publisher, founded in 1923 and now owned by Penguin Random House (hey, who isn’t?). Dial has always been adventurous, bringing us James Baldwin and Norman Mailer in their early years and even coming out with Elizabeth McCracken’s The Giant’s House in 1996.

Well, charmed and affected by Dalí’s painting, I finally read the book, where he battles for the soul of modern art by defending the architecture of Gaudi against the criticisms of Le Corbusier (who Dalí assures us, eventually relents and develops good taste) and sings the praises of Vermeer over Piet Mondrian, in a delightful few lines that remind me of Vonnegut:

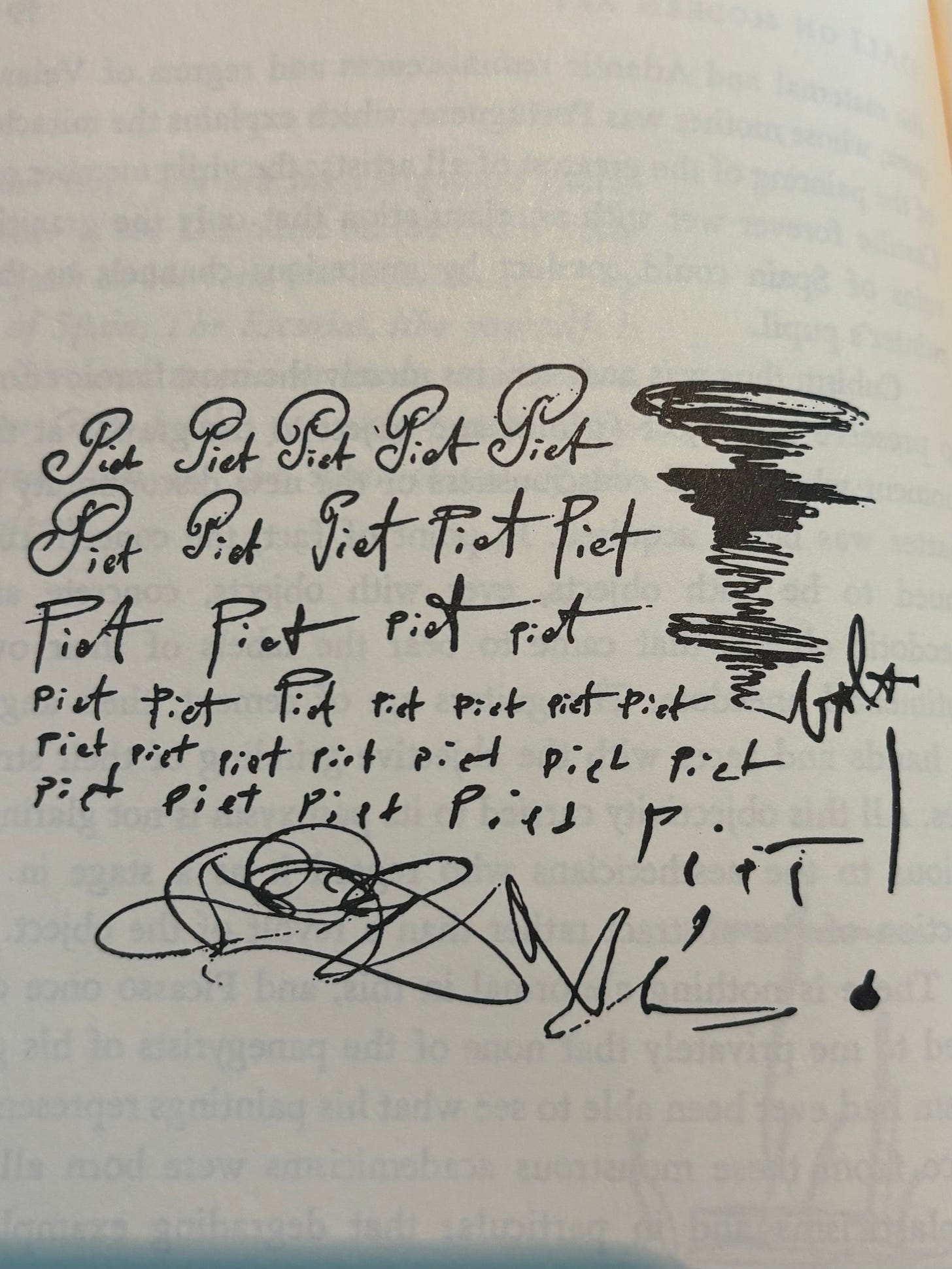

“Completely idiotic critics have for several years used the name of Piet Mondrian as though he represented the summit of all spiritual activity. They quote him in every connection. Piet for architecture, Piet for poetry, Piet for mysticism, Piet for philosophy, Piet’s whites, Piet’s yellows, Piet, Piet, Piet………………………….Piet, Piet, Piet, Peep, Pity, Piet. Well, I Salvador, will tell you this, that Piet with one “I” less would have been nothing but pet, which is the French word for fart.”

Well, I like Mondrian but here I almost see Dalí worrying over the same qualities that had me hesitant to bring up the master here — when an artist is so widely praised, sold, resold, reproduced and imitated there’s a certain cheesiness to piling onto the success. I felt a bit embarrassed by going to an art fair with hundreds of booths run by quality galleries, featuring thousands of paintings, drawings and sculptures of all sizes and then coming back here to tell you that it was Dalí who knocked me on my ass — and late 1970s Dalí at that!

As if anticipating my dyspepsia, Dalí ends the book with a bit of a rumination about success and money that seems prophetic from the vantage of 2024:

“I have always been dazzled by gold, in whatever form it appears. Having learned in my adolescence that Miguel de Cervantes, after having written his immortal Don Quixote for the greater glory of Spain, died in wretched poverty, that Christopher Columbus, after having discovered the New World, had also died under the same conditions, and in prison to boot, already in my adolescence, as I say, my prudence strongly counseled me two things:

to have my prison experience as early as possible. And this was done.

to become to the greatest extend possible a bit of a multimillionaire. And this, too, was done.

Dalí then talks about how money confers freedom and for those who avoid the vulgarities of commerce in creative life, he concludes, “….the pure critics who have consistently despised money and been afraid to dirty their hands by touching it may rest assured:the abstract values they defend in modern paintings will inevitably be converted into absolutely clean, wholly inoffensive and immaterial money. It will be purely abstract money.”

My friends, in think that in 1957, Dalí foresaw the NFT!