The Middlebrow doesn’t often hesitate to have opinions, but looking at the news out of the Middle East does inspire caution. It’s hard to imagine that the world, or the few dozens who read these musings regularly, will actually benefit from another opinion about Israel and the Palestinian people.

I do know, living in New York City, that having a very public opinion has become an identity for a lot of (mostly younger) people. There have been scores of public protests and a decidedly liberal embrace of the Palestinian cause despite the inarguably illiberal character of Palestinian leadership. This identification is, in my view, a mistake.

What I see in the streets and online makes me recall the movie Reds about the American journalist John Reed, who was radicalized into socialism after covering the Bolshevik Revolution but was, despite his formidable mind, unable to truly come to terms with how those events were perverted by Stalin.

Like many, I grew up hearing that “one man’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter.” It’s a truism that’s at the root of all violent conflict over land, resources and self-determination. But the world is not usually neatly divided into evil empires and plucky rebels, like in Star Wars. Ambiguities abound in almost every conflict, even between Rome and Carthage. You can’t attentively read The Iliad and The Odyssey without realizing that there are heroes and villains on both sides, as well as blame to spread and points to credit all around. That Fulgencio Batista was a brutal dictator in Cuba is not a good reason to don a Che Guevara t-shirt in 2024.

History will sometimes ask us to choose sides, particularly when the lives, freedom and dignity of others are at risk. One writer who chose authentically was Albert Camus who, along with fellow existentialist Jean Paul Sartre, edited the journal Combat to support the French resistance against the Nazi occupation during World War II.

In Camus you have a very interesting figure who embodies all of the contradictions of art and politics. He would have fought in the resistance, had he not been rendered incapable by tuberculosis, but he contributed how he could, at considerable risk. Camus did his part as a champion of freedom against fascist oppression.

At the same time, Camus was born and raised in French Algeria, a colony where French authorities treated the indigenous population brutally. So France found itself simultaneously occupied at home, while an occupier abroad and Camus, French to the core, supported it all, with reservations.

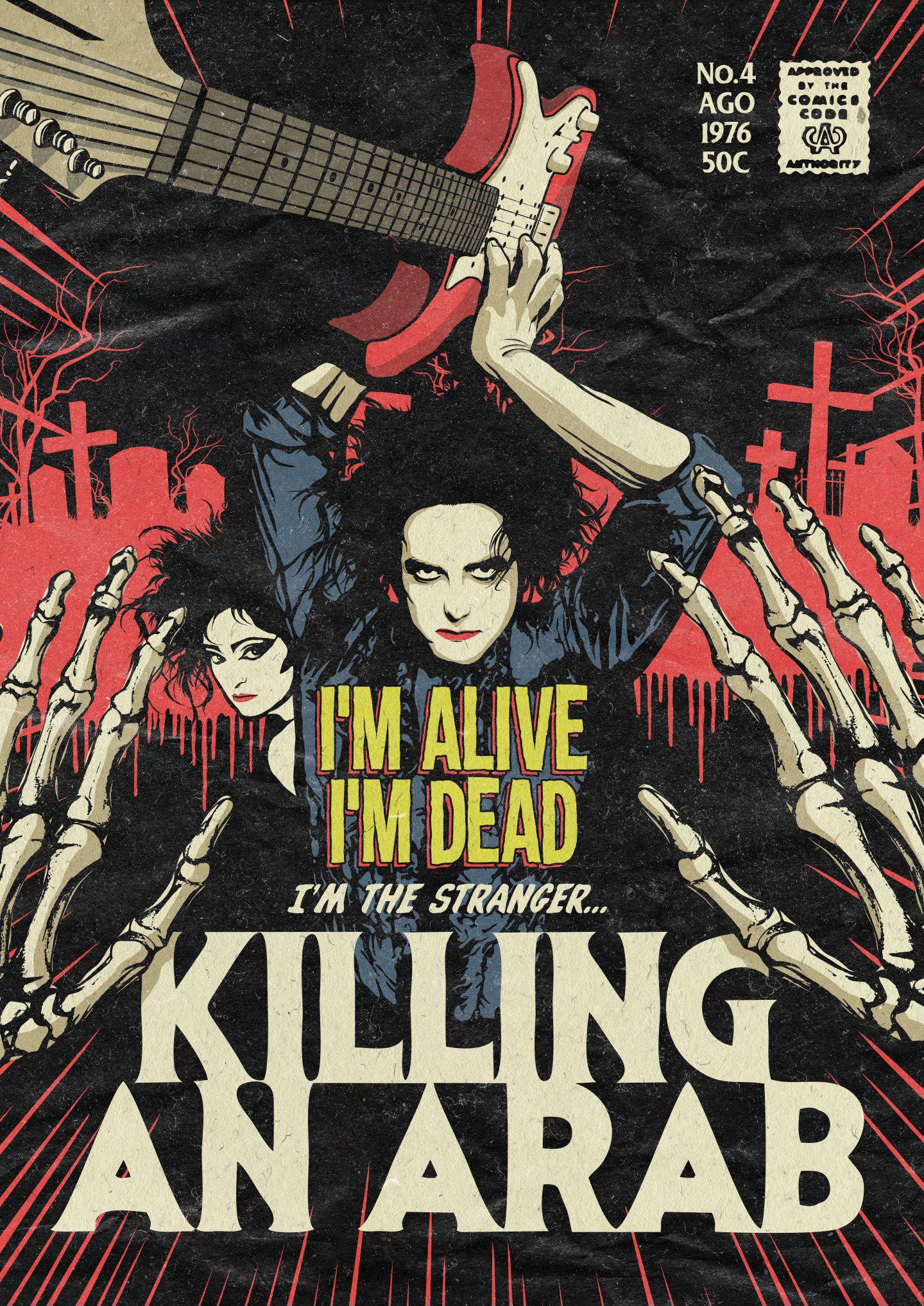

To me, those reservations come through in The Stranger, his most famous work of fiction. At the start of the novel, a man named Meaursault is unable to summon tears or sadness over the death of his mother. Later, he nonchalantly shoots and kills an Arab who is walking on the beach. At his trial, he is unable to explain himself and blames his actions on the heat and the brightness of the sun.

This murder, without feeling, motive or remorse has captured the imaginations of readers, artists and philosophers. It is dramatized by The Cure in their album, “Staring at the Sea.”

Of course, the event proposes big questions like “What is guilt when there is no remorse?” and “What is freedom when something so trivial as the weather can motivate even our most extreme choices?” What’s less often pondered is whether there is a political dimension to this. I suspect that on some level, a writer as thoughtful as Camus realizes that the dehumanizing effects of the French occupation and the view of the native Algerians as “others,” could also motivate Meaursault’s deadly indifference. If that’s the case, our political choices, especially when it comes to conflicts and occupations, really matter when it comes to who we are, what we do and why we do it.

To bring it all back to the start, I think the meaning of The Stranger obligates us all to ask how our politics define us and to examine what we might be signing onto when we take to the streets chanting “from the river, to the sea,” as citizens of a first world western democracy, an ocean removed from the very real people whose conflicts are nuanced in ways no slogan can capture. And, don’t worry about how your political opinions will affect the situation on the ground there, or even U.S. policy, because they likely won’t. Ask how your declarations define who you are, how you think and, ultimately, what you might be capable of doing.

Jean Larteguy’s The Centurians is another excellent depiction of colonialism in Vietnam and Algeria. I am convinced Hamas thinks they’re fighting the war against the French in the 1950s but the Israelis are fighting a cery different war. It will take a lot more violence for the two views to come into alignment.