Yesterday, the Renaissance son headed uptown to make an iPhone documentary with his friend, an up-and-coming alchemist working his sorceries around the Flatiron. Scholar Wife read aloud a description of the movie The Sweet East, and I interrupted her to say I wanted to see it. Off to the IFC Center (once, The Waverly) we went. What immediately grabbed me about the synopsis of the film was its similarity to Candide, one of my favorite books and one of the few that (along with The Great Gatsby and Heart of Darkness) that I reread every few years.

In The Sweet East, a South Carolina teen on a field trip to Washington, D.C. narrowly avoids a Pizzagate style massacre and is separated from her classmates, and her iPhone in the process. She falls in with a gang of Antifa activists from Baltimore, tags along with them on a raid to fight Nazis outside of Trenton, New Jersey, falls in with the Nazis, escapes from them to New York City, joins the cast of an independent film and then a rural Muslim brotherhood, and then a Christian monastery and finally, home.

New Yorker critic Richard Brody saw The Wizard of Oz in it, and I get the reference, but that’s a long way from Voltaire’s vicious satire of life on Earth and the moral failings of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who argued at times that if God is perfect and God created the world and the reality we all inhabit must be the best of all those possible.

Like Voltaire’s title character, Lilian (played really well by Talia Ryder, our new Winona Ryder) is a student. Voltaire’s teacher is Dr. Pangloss, who believes that “all things are for the best,” including absurd notions like humans having bridges on their noses to hold up glasses and looking for the bright side of mass casualties caused by earthquakes in Lisbon. Lilian’s Pangloss is a white supremacist university professor named Lawrence, who believes in the myth of a superior, but lost United States who tries to teach Lilian to hate degraded, contemporary culture.

One of the shared themes here, which makes the satire of Candide and The Sweet East so biting is that older people with influence and power will continually try to sell bad ideas to curious and intellectually agile young people. In The Sweet East the main lessons are racist nostalgia, which is just as wrong as clueless optimism was to Voltaire, and also as wrong as the “survival of the fittest” mantra that Lieutenant Dan tries to teach Forrest Gump in another Candide retelling.

Throughout The Sweet East, Lilian bounces between Balkanized subcultures from the Trustafarian left to the racist right, to the dogmatically religious and the devotedly artistic. In the divisions of those separate cultures lies the potential for horrific violence and the ubiquity of guns makes it all possible at almost any time.

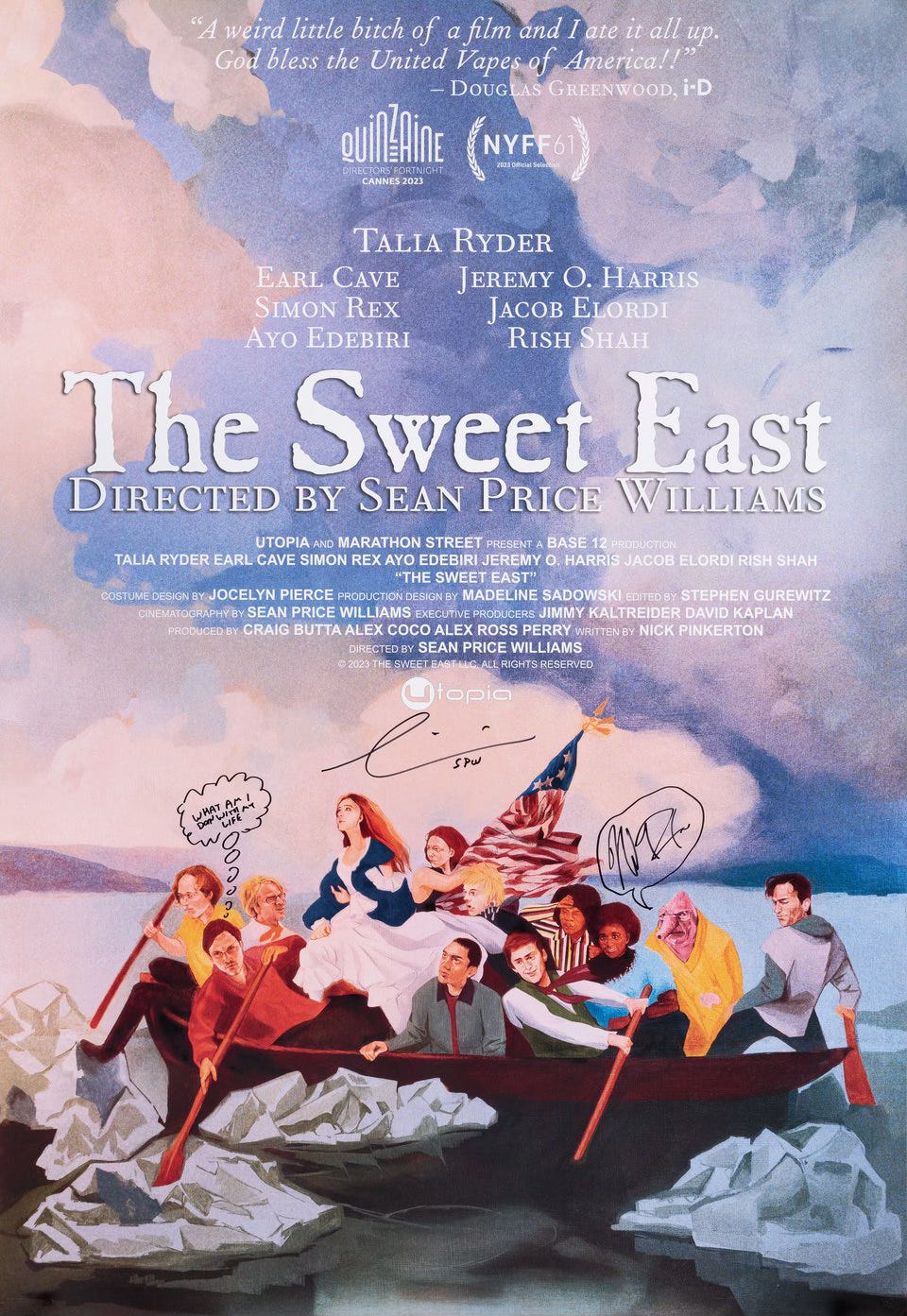

Director Sean Price Williams draws amazing performances out of a largely new cast. A longtime cinematographer, he also creates amazing visuals in his directorial debut. Screenwriter Nick Pinkerton brings depth of literary and film references to the story. It’s well worth seeing.

There’s a neat bit of symbolism, which also serves the plot, right at the beginning. Lilian is, at the first hint of danger, separated from her iPhone. This has to happen as the ubiquity of the phone as both lifeline and tracking device would make her disappearance from her regular life impossible. When Voltaire was writing, people could really disappear into the wider world. They could not be reliably followed or tracked. People could also journey to places so remote that they could not get back home. This was true as well when Terry Southern sent up Candide as Candy and when Winston Groom wrote Forrest Gump (it’s the novel, more than the movie, where the connection to Candide is clearest). But in 2024, it’s very difficult for people, especially young people, to become untraceable.

I wonder if screenwriter Pinkerton, who is also a film critic and historian, is aware of Southern’s Candy as The Sweet East uses sexuality in ways that Southern did but Voltaire did not. Southern’s long connection to Hollywood makes this at least possible. In his New Yorker review, Brody views the film as a commentary on both commercial Hollywood and the present day independent film scene, with some nostalgia for earlier periods of both.

Separating Lilian from her cell phone gives her time and space to think about what she’s experiencing and how she should deal with each situation, which are all fraught with danger, couched in the soothing assurances of well-meaning caretakers. Without giving the ending away, watch for the re-emergence and ubiquity of the iPhone in the movie’s later scenes. There’s definitely commentary about “real life,” there.

The Candide story, about intellectual rebellion in the face of absurdity, is always worth thinking about. The Sweet East is a great way to revisit it, and a wonderfully different independent film.