The Whitney's "What If?"

A new exhibition ponders the possibilities for American contemporary art had surrealism guided the Post-World War II decades.

Sixties Surreal, the new exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art explores an alternative art history. Curators Dan Nadel, Laura Phipps and Elisabeth Sussman ponder the possibilities of surrealism as the guiding force for American art in the 20th century and beyond, asking: “What if it were subject matter, not form, that had been primary to artists in those crucial Atomic years in the United States?” That question is the crux of the argument in their introductory essay “Feelings are Things,” which nicely sums up their deeply affecting collection.

Our lived art historical experience is that cubism gave way to abstract expressionism which gave us pop art and minimalism, giving us the liberation of art for its own sake and grounding us in form as a way of making sense of the shifting physical, social, political and economic landscapes around us.

Abstract Expressionism had a little help reaching dominance, of course. A young Central Intelligence Agency, perhaps more creative and thoughtful than the intelligence state it spawned, secretly funneled money into the art world to promote the works of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, Mark Rothko and others around the globe. The artists were not aware, but the CIA gambled that it could use wealthy individuals and public front agencies to promote a celebration of American creativity and individualism as superior to what it considered the bland realism of state sponsored art being produced in the Soviet Union. The CIA promoted AbEx abroad as an innovation as American as jazz music.

American surrealism, with its roots in Europe, Africa, Asia and Native American folklore got no such support and really never could have because surrealism is rooted in revolutionary thinking and is nurtured by artists and writers struggling to break free from the restraints of government, material needs, social order, religion, work, war, sex and gender (all the pillars of authority a good intelligence agency is designed to support). If abstract expressionism explores the forms that make the world around us, surrealism explores the parts of our psychology that we so often repress just to get by in it. Then, the surrealists encourage us to let all of that out, even at risk of social cohesion, material comfort or economic efficiency.

The surrealist point of view is a universal condition that shows up across time and cultures. There are elements of the surreal in most ancient tales, especially the Greek myths as retold by Ovid and in the more magical elements of Shakespeare. In its more modern, European heritage, it evolved out of Dada-ism, which specifically rejected the horrors of late 19th century conflicts and World War I. Dada-ists like Alfred Jarry satirized political strongmen while leaders like Marcel Duchamp, Anthonin Artaud and Tristan Tzara were explicitly trying to remake society to prevent future wars.

As recalled by Gertrude Stein, the artist Manolo, sometimes considered a surrealist, always a friend, stopped off on his way to war, after his conscription, and sold his horse and rifle to fund a voyage to Paris where he would begin his artistic career. In that, Manolo is a hero of the movement as he lived the conviction that the power structures that lead us into war can and should be resisted.

Collectively, the works in Sixties Surreal question everything about how we make the world work. And, for some of the artists, looking at a world of injustice, war and poverty, surrealism is realism just like, to Franz Kafka, The Trial is a realistic account of being born into a world where we all start out convicted of a crime we never committed.

“I do not need to go looking for ‘happenings’, the absurd, or the surreal, because I have seen things that neither Dali, Beckett, Ionesco, nor any of the others could have thought possible; and to see these things I did not need to do more than look out of my studio window above the Apollo theater on 125th Street,” surrealist American artist Romare Bearden told critic Dore Ashton in a 1964 interview.

As you might expect, American surrealists of the 1960s pushed against every form of authority they encountered, be they social, religious, racial, political, economic or even personal.

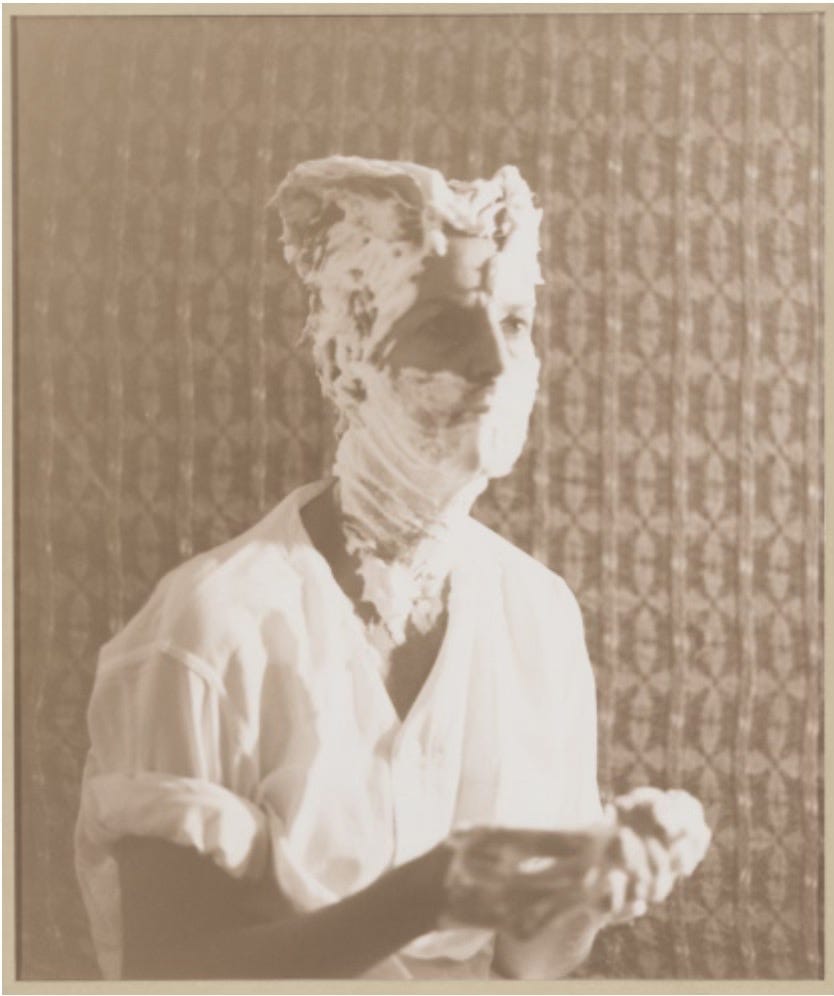

The prankster/imitation master Sturtevant, represented in the exhibit by her own photographic homage to Duchamp and Man Ray would, a year after she produced this photo, scandalize and satirize the art world by by completely duplicating Swedish artist Claes Oldenberg’s 1961 gallery installation called The Store. In Dada-ist fashion, Oldenburg recreated an American five and dime store in plastics and ceramics and put it forward as art. In 1967, Sturtevant meticulously recreated Oldenburg’s living sculpture, just adding her name to the title, calling it “Sturtevant’s The Store of Claes Oldenburg.” Sturtevant not only raised the question of what art is or could be, but she pushed the boundaries of how artists relate to each other. The stunt cost her Oldenburg’s good will and friendship.

It’s emblematic, though, because the artists in Sixties Surreal were not organized into any formal collective or hierarchy that resembled the subculture that Andy Warhol managed to build and nurture around Pop Art. What’s common in this art is a sensibility, not shared social networks. Indeed, Oldenburg, represented here as a surrealist, is often considered a Pop Artist. Marisol, one of Warhol’s Art Stars, shows up in Sixties Surreal as a completely independent artist with a stunning point of view that caught the mind and eyes of Natasha Gural.

There are works of surrealism from the American west, from Native American reservations, from Chicago and from small towns. Artists explore new mediums like fiber glass sculpture and the emergent technologies of portable film and video-making. I was particularly moved by the video/performance art pieces of Mike Henderson caught in his reel Doofus, where he portrays stylized versions of the characters he encounters in daily urban life.

Whether its opposition to the Vietnam War, a desire for freedom from the social strictures of Catholicism or women exploring their gazes without men in paint, video and photographs, what brings the surrealists together is the recognition that something is wrong with the way we’re choosing to life, or with the choices we’re never given. These artists recognize the tragedy of our absurd conditions and how so many of us waste what may be our one spin on the planet in the service of mercantile and militaristic aims.

The show asks us to consider if we might have been better off had we given the surrealists more sway in our discourse and society. I tend to think it would, if only because the surrealists start conversations that most people never consider.

Is it too late? Happily, our curators (Nadel, Phipps and Sussman) leave us with a hopeful message:

“As we are all too aware in our current moment, both repression and freedom thrive in ambiguity. But whereas the politician might use ambiguity to obfuscate intent, the artist might seize upon it as a way to encompass contradictory feelings -- to make something that is generous enough to speak to people in the language they bring to it.”

It’s happening every day, all around us. Sixties Surreal reminds us of the “2020s Surreal” in the making all around us.