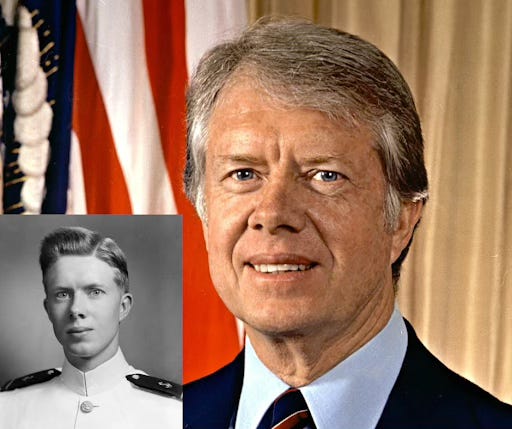

Welcome Back, Carter's Legacy

A Jimmy Carter op-ed from 1989 exposes unexamined facets of the former president's personality and American culture from the late 20th century.

The Carter Center has preserved the former president’s New York Times op-ed “Rushdie’s Book is an Insult,” which is the kind of headline you would expect associated with a radical mullah from the Middle East, not a former American president, acting worldwide as an unofficial face of our nation’s diplomacy. This bit of literary opinion was not highlighted or examined during the recent celebration of Carter’s life and service, following his death on December 29th, 2024.

The subject of the piece was, of course, Salman Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses, a tale of religion and the immigrant experience that scandalized the Muslim world and that Iran’s dictator of the moment, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, reacted to by issuing a “fatwa,” or formal religious command for Rushdie to be executed. The threat was so real that attempts were made on the author’s life and he had to go into hiding. Though fervor for Rushdie’s life waned with time and Rushdie emerged from hiding, the fatwa has never been rescinded and factored into the author being stabbed in the eye during an August 2022 in tony Westchester.

Naturally, Carter doesn’t endorse the fatwa, but he amazing endorses the sense of persecution behind it, while managing to drag film auteur Martin Scorcese into it as well (and, by extension, novelist Nikos Kazantzakis.)

Here’s Carter, in his own words:

A negative response among Christians resulted from Martin Scorsese's film, ''The Last Temptation of Christ.'' Although most of us were willing to honor First Amendment rights and let the fantasy be shown, the sacrilegious scenes were still distressing to me and many others who share my faith. There is little doubt that the movie producers and Scorsese, a professed Christian, anticipated adverse public reactions and capitalized on them.

''The Satanic Verses'' goes much further in vilifying the Prophet Mohammed and defaming the Holy Koran. The author, a well-versed analyst of Moslem beliefs, must have anticipated a horrified reaction throughout the Islamic world.

This reasoning, from a former president, is depressing and disappointing, though we heard echoes of it in response to the massacre of the editorial staff of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in 2015.

Carter’s endorsement of religious offense at The Last Temptation of Christ and The Satanic Verses was parochial and illiterate. Neither work was produced specifically to offend, or even to capitalize on offense. These works were created specifically to question prevailing views and to get their audiences to ask hard questions.

The Last Temptation of Christ tells the story of the life of Jesus by treating its protagonist as a human with realistic psychology, rather than a divinity. As Jesus, Willem Defoe creates a relatable character and the script, following the novel closely, gives us the story of a man tempted by sin, who even imagines, while dying on the cross, that he might have been better off denying his destiny and living with Mary Magdalene. He also dreams or hallucinates about having sex with her, a sensation likely superior to being crucified.

In The Satanic Verses, author Rushdie depicts the Islamic prophet Muhammad in dialogue with pagan entities and also features parodies and complaints about muslim law. He strongly implies that on his deathbed, Muhammad believed in and communed with pagan deities, contradicting Islamic orthodoxy.

If an artist wants to inspire followers of a Messianic religion to think, dramatizing the life of that religion’s Messiah is an important starting point. Obviously, the life of Jesus has been depicted, over and over throughout centuries, from medieval miracle plays through Jesus Christ, Superstar. This can be done with deep fealty to religious tradition, or to celebrate those ideas, but if the intention is to make people question or even modify their beliefs, then the artist should probably take some liberties. The humanizing of Jesus in The Last Temptation achieves that, even if it offended some, like the former president.

People writing about Islam or depicting it in art risk running afoul of Islamic edicts against depicting the prophet in drawing or telling lies about his life, which is the accusation made against Rushdie. An obvious answer is to not risk offending people by just not bothering, which allows the idea of Muhammad to exist in the world, and even to influence non-Muslims, in a kind of one-way conversation.

Carter seems to be criticizing a profit motive for giving offense, which he deems less worthy than the religious motive for taking umbrage. But artistic intent should sit on least equal ground with religious belief as both art and religion are methods people use to pursue knowledge generally forbidden by metaphysics.

Without regard for the importance of artistic exploration (its much easier to criticize commerce), Carter moves on to the familiar argument that the right to say something doesn’t make it right to say those things:

“While Rushdie's First Amendment freedoms are important, we have tended to promote him and his book with little acknowledgment that it is a direct insult to those millions of Moslems whose sacred beliefs have been violated and are suffering in restrained silence the added embarrassment of the Ayatollah's irresponsibility.”

Somehow, Carter avoided harsh criticism for his stance. This may be because so many people, in the late 1980s, tried to defend Rushdie’s right to publish without endorsing his work (which few of them had read, in any event). The mainstream reaction of the moment, similar to how people reacted to the Charlie Hebdo murders, was to vaguely defend western rights while apologizing to those with hurt feelings.

Amy E. Schwartz of The Washington Post responded with a rare retort titled “Jimmy Carter Should Know Better.” Schartz cuts deep in defense of the creative arts and we could use more thinkers like her in contemporary media:

“Suddenly there seems to be a question, not of whether Rushdie should be censored, but whether he, well, ought to have done something so insensitive as to disrespect Islam. How on earth has the debate gotten to this point? When a former U.S. president chimes in with a dismissal of Rushdie's serious artistic intent as "insulting," and suggests we are holding our nose on this -- as we might do in defending a neo-Nazi rally or a pornographer -- then maybe it's time to restate some things about censorship and artistic freedom that two weeks ago seemed numbingly obvious. Mr. Carter accuses the novel of "vilifying the Prophet Mohammed and defaming the Holy Koran." Sir Geoffrey says Rushdie "compares Britain with Hitler's Germany" (a characterization Rushdie contests.) Is it too much trouble to remind people that novels -- good ones, anyway, as opposed to apparatchik trash -- do not take positions? That they are not political arguments but explorations of life and experience?”

Carter’s unnecessary criticism of both Scorcese and Rushdie and his weak defense of art and expression stand at odds with the image of the thoughtful and kind former president that recent celebrations have left behind. This was a shameful op-ed, unworthy of any elected leader of an open society, and its implications should be part of any appraisal of Carter’s political and cultural legacy. Sorry, Jimmy, you let us down.