What is Progress?

And... has western society grown timid?

If you'll forgive a quick visit to the world of superhero comic books, please consider with me Fantastic Four #1, widely considered the birth of the Marvel universe as it introduced Reed Richards, Sue and Johnny Storm and Ben Grimm. The premise is that the genius Reed had designed and built a space craft. Ben would pilot it. Reed's girlfriend and her little brother would serve as crew. They would explore beyond our atmosphere together, in 1961.

This was a premise straight out of the pulp science fiction of the earlier part of the century (and even the 19th century), where people commonly journeyed into space, traveled through time, altered their physiology to let their Ids roam as monsters or reanimated dead tissue into new forms of life. All of these things were done without government regulation, concerned shareholders with ESG mandates or any permission at all from society at large.

The Fantastic Four were, of course, exposed to disfiguring radiation that gave them all super powers. In all these stories, unintended consequences abound. But the germ of the idea, coming right out of the Industrial Revolution, is that any individual with intellectual, mechanical and material means can pursue their ambitions without much thought for how the results might alter life on Earth.

In the real world, even Elon Musk needs permission to fire rockets into space. When Chinese biologist He Jiankui, frustrated with the world's regulatory slow walking of gene editing, went ahead and used CRISPR technology to alter the genes of willing human subjects on his own, the world condemned him. But Jiankui did have a point -- we can actually do a lot more with gene editing in humans than regulators allow. The technology is there, and it works. Society just doesn't allow its use.

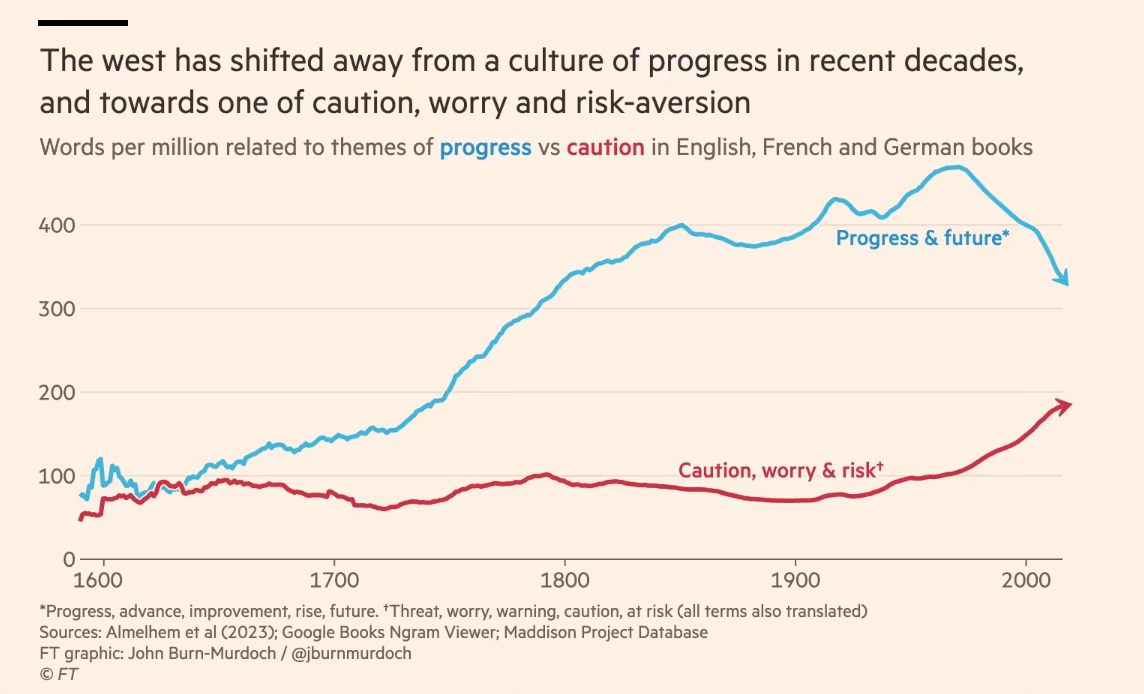

There is a sense, as we have given up stories of rogue initiative in favor of working within complex social, economic and environmental systems, that people have shifted focus from grand achievement to risk mitigation and caution. Last week The Financial Times published results of a study that analyzes the content of books to show that we have shifted, since the Industrial Revolution, from a focus on progress to one based on caution.

I want to say this seems true. But, a few words of skepticism:

First, analyzing books by frequency of words is tricky. A satire of progress, like Voltaire, might read as an endorsement. A work of societal decay, like Meim Kampf, might read like a progressive textm given its strong wording and ambitions. Computers can't really read, after all.

Second: While it might seem, especially in the United States, that we have abandoned grandiose goals like colonizing the moon or building the world's tallest skyscraper or mining for the world's largest diamond, there are certainly people willing to break social norms in attempts to do the impossible. There are homemade submersibles that try to visit the Titanic. There are dissident Chinese scientists willing to risk prison to show that gene editing works. There are Silicon Valley billionaires pursuing transhumanism (the use of technology to enhance mind and body) and immortality.

That said, the tone of conversation has shifted and that it's been changing ever since we entered the age of nuclear weapons, a permanent age of history where humanity can destroy itself with technology. We are more risk averse because we face greater risks, we tell more complicated stories because we now see seemingly disparate issues as connected. If somebody wants to build the world's tallest skyscraper or stage a coast to coast road race like the old Cannonball Run, somebody else is going to ask about the carbon footprint of such an endeavor -- and it's a reasonable question!

All this brings us to the question of how we define progress. Because there's one definition of progress that follows a form of conquering reality and bending it to our wills -- defying gravity and going to space even if the sun's rays turn us into rock-like monsters with superhuman strength and there's another definition of progress where we live in harmony with nature, don't seek to alter it to our preferences and instead accept that we are part of it and bound by laws that are larger than us.

Contemporary environmentalism, focused on manmade climate change, has introduced concepts of scarcity and limits into our policy discussions, and those ideas have stuck in both the popular imagination and in the discussions among government officials, investors and business leaders. Previously, the argument for market-based economies and capitalism is that because these systems create wealth and combat scarcity, that there are no zero-sum games. Capitalism might create massive inequality, goes the reasoning, but it also create massive, self-perpetuating value so that even people who get the smallest rewards are drawing from a growing pool of incentives. Contemporary environmentalist thought is based in notions of material scarcity and natural limits to economic growth.

In Foreign Policy, Jun Arima, a professor at Tokyo University and Vijaya Ramachandran, director for energy and development at the Breakthrough Institute, argue that the doomsday language of climate change activists has backfired and hurt the credibility of the movement:

Sticking to an unrealistic temperature target has severe economic and geopolitical effects. Panic over not reaching the target has led to a radical push for an immediate phaseout of fossil fuels, ignoring the fact that they still make up 80 percent of the world’s primary energy supply. That call is being led by rich countries that have become wealthy using fossil fuels and continue to gobble up oil and gas—and which now want to restrict less-developed countries from using these fuels to lift themselves out of energy poverty, a primary reason for their destitution. Development advocates are rightly calling out these unfair policies, enforced through institutions such as the World Bank, as eco-colonialism.

Unrealistic temperature targets combined with continued high consumption of fossil fuels has meant that there is little to no carbon budget available for the poorest countries to grow their energy use. Sticking to the goal of freezing emissions—or even targeting negative emissions to compensate for any overshoot—turns global economic activity into a zero-sum game.

Throughout history, there have been many apocalyptic predictions and so far they have all, by definition, been false. From the “population bomb” claims of the late 1960s, which were based on economic ideas of Malthusian scarcity, to technological troubles like Y2K, every prediction of destruction has turned out wrong, though there have been some close calls and sometimes the alarmism has triggered mitigating responses, so it has uncredited value.

At the same time, Arima and Ramachandran make an interesting point — if the United Nations and the larger economies are going to tell developing nations that they cannot benefit from the world’s energy reserves the way we did, that they cannot increase meat consumption, increase vehicle and home ownership or travel the globe freely the way we do, and it turns out that the challenges of climate change are not so insurmountable to justify such standard of living sacrifices, people are naturally going to resist.

Most of us exist in a middleground where we are both unwilling to really stick our ambitions into reality's face and to build that Tower of Babel, but are also unwilling not to fly to a sunny place for vacation, when we can.

But, again, what is progress? Because, despite all of this, The Middlebrow sees no shortage of ambition even if we don’t discuss it with the triumphalist language of the past.

"as we have given up stories of rogue initiative in favor of working within complex social, economic and environmental systems" - The change from nineteenth century "classic" novels to late 20th-century media and today's storytelling strikes me as very stark. Just for one example, even with an ecological focus, "My First Summer in the Sierra" is about one person's perceptions and lessons, while "The Overstory" has no single main character. In YA literature, the Keeper of the Lost Cities series constantly frustrates me because the main character (female) has to run all her ideas by someone. The message is that any individual, no matter how powerful, can make misjudgments; we all need friends. But it's frustrating to wait for chapters to roll by before she can act on a hunch. A nineteenth-century novel would have had her launched on the whaleroad at the first thought of it. It's funny. I agree in principle with the "systems" books, but it's more fun to read and get carried away with rogue individuals.