Since late 2023, pundits have pondered purportedly perplexing public perceptions about the United States economy. Most of the data is good, they say, but when people answer polls they consistently say that the economy is performing poorly. What gives?

“When it comes to the economy, the vibes are at war with the facts, and the vibes are winning,” writes Greg Ip of The Wall Street Journal. He suggests that some people just don’t know what they’re talking about:

“Lower inflation means the level of prices is still rising, just more slowly than before. People sometimes conflate inflation with the level of prices and believe inflation is getting worse because the price level keeps going up (it rarely goes down).”

Careful, Greg! The Middlebrow isn’t so sure you’ve got this right! Price levels are snapshots of prices at a given time. This iPhone costs $1000 at the Apple Store today — that’s a price level. If it costs $2,000 at the Apple Store tomorrow, that’s inflation and its rate, measured in days, is 100%. If it costs $1,500 on day 3, you have 50% deflation in one day, but 50% inflation measured from day 1. You cannot say that the price of something went from $1,000 to $2,000 and then fell back to $1,500 and tell somebody who first saw the $1,000 price that “inflation is falling.”

Greg is confusing inflation, a phenomenon where prices are generally rising, with the rate of inflation, which is our measure of how fast prices are going up. Inflation is, by definition, always going up. If there is any inflation to measure, it means that prices are rising. If prices are falling, we use the word deflation.

In the U.S. right now, the inflation rate is around 3%, year-over-year. Last year, the inflation rate was 6% year-over-year. It’s not accurate to tell people that “inflation is going down.” You can say the rate of inflation is slowing. Even then, given that the Federal Reserve Bank of the United States targets 2% inflation, our current situation is rising 50% faster than we’d like, the equivalent of driving 45 mph in a 30 mph zone.

And, inflation compounds. To go back to our iPhone example, if our $1,000 gadget experienced inflation of 10%, the price goes up to $1,100. If the price went up 100% to $2,000 and then only went up 10% the day after, it would cost $2,200. You can say the rate has fallen all you want, but the inflation on a higher base is going to cost more in real terms.

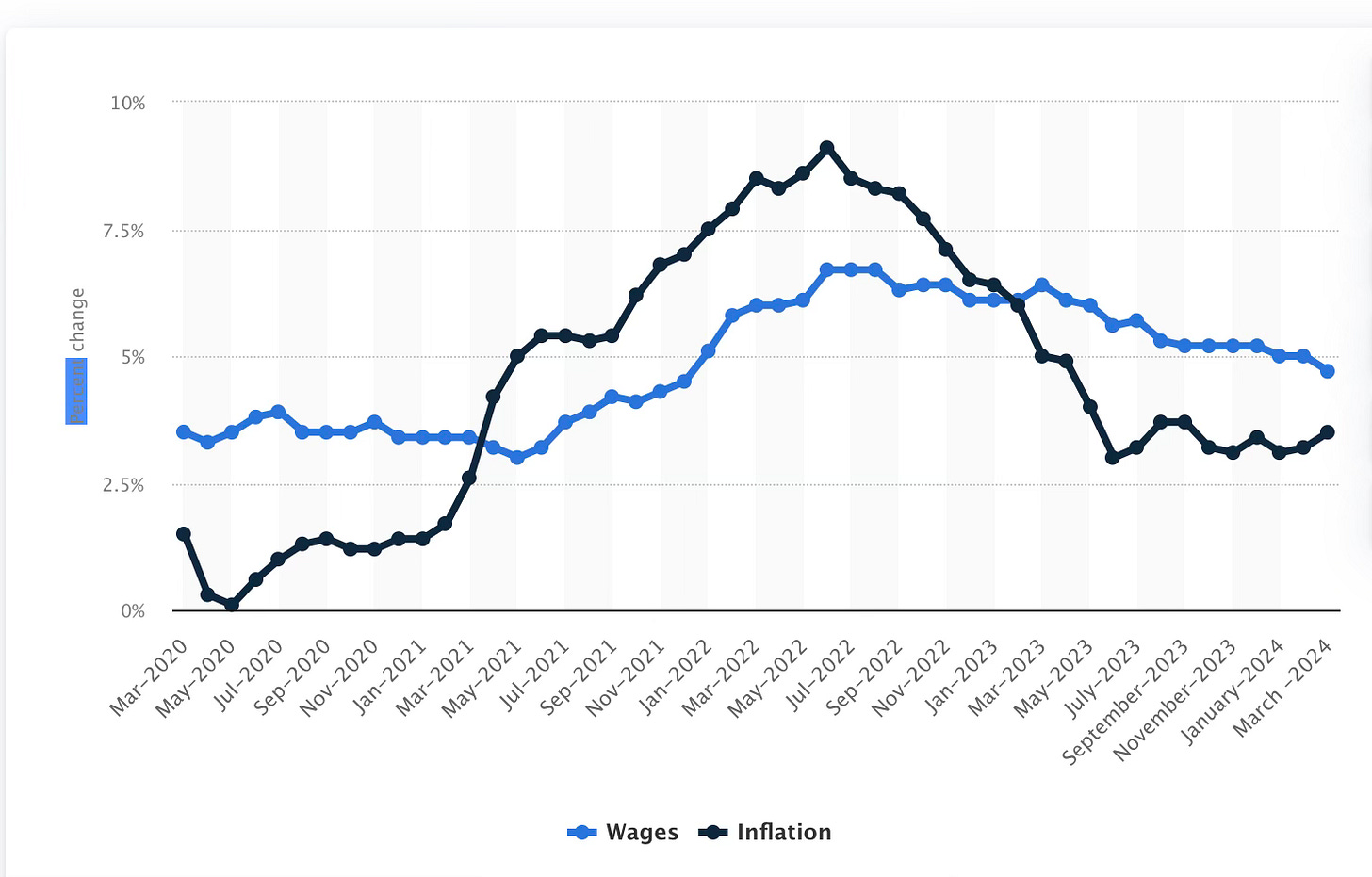

U.S. inflation spiked at around 9%. The rate has fallen since, but that big jump in prices is baked in. People looking back to pre-COVID prices are right to register discontent. This is clearly not people misunderstanding inflation. They understand it deeply.

Another claim is that people are either lying or convincing themselves they are miserable, based on political tribalism. FTI Consulting argues that: “Simply put, more Americans view the economy as doing poorly when 'their guy' isn't in the White House irrespective of the macro-level data.” They say this trend goes back to the Obama administration, though it seems more likely to me that the Financial Crisis, which highly politicized the economy, is the likely culprit. Economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman also believes this.

There’s probably something to this, as we all emphasize the positives or the negatives to suit our larger agendas. But there’s enough wrong with the economy that negative sentiment can’t be dismissed as whining from the side out of power. Anyway, economic data is politically agnostic and this kind of thing cuts both ways. Obama suffered for Bush's recession, which was in part caused by regulatory decisions made by Clinton. Meanwhile, Trump benefitted from becoming president in 2016, when the slow post Financial Crisis recovery finally picked up steam. Biden inherited a disaster but reaped the rewards of the stimulus package that Trump provided to deal with it and the next president will be aided by spending from Biden’s $1.3 trillion infrastructure plan. People know and understand this. It’s actually the media that ties economic conditions to specific presidents, as a sort of shorthand.

The media is another potential culprit. Brookings has been arguing all year that poor economic sentiment is the result of negative reporting about the economy. This is another variation of the political polarization argument, though I think it makes sense for the press to be more skeptical in its coverage of business and the economy after the 2008 crisis. What’s being viewed here as negative journalism might be the press asking the right questions. That would mean people are getting accurate information from “negative” reports.

If it’s not ignorance, partisanship or the press causing people to “misunderstand” their economic conditions, we might consider that people aren’t missing anything at all and that their feelings are both honest, and justified.

When the COVID pandemic hit, the government rightly responded with Keynesian stimulus and emergency spending to help the suddenly unemployed. Businesses over-fired in a panic and then rushed to re-hire workers as a brighter future emerged. Given continued risks or illness and with bolstered savings accounts, some workers refused to go back, at least at anything close to their original terms of employment. There was, briefly, a period where wages jumped, employers had to pay signing bonuses and offer all sorts of perks. For a few months, after decades of being left behind, workers saw real gains. Jobs that hadn't previously offered insurance, equity or paid time off, suddenly did. There was briefly a new reality where power had shifted to labor.

Inflation took off almost immediately and outpaced wage gains from the spring of 2021 all the way to the spring of 2023. The rate of inflation outpaced the rate of wage gains by so much that, if you compare purchasing power today to before the pandemic, most workers haven’t gained anything. People were whiplashed.

The promise of being able to get ahead through hard work was replaced by the same old.

And, where did the money go? Well, big producers like PepsiCo used a “price over volume” strategy where they hiked prices to improve margins, adding to earnings even as sales were stagnant. Corporate margins widened considerably as this practice proliferated throughout the economy. For the average American it was like getting a raise only to have it stolen by the grocery store.

Then there are the things that economists don’t measure — employers are clawing back some of the concessions they made during the pandemic. Remote work became hybrid work. “Come to the office when you need to,” became “Come in three days a week,” or even five. The rapid shift-back in power from labor to employers isn’t captured in economic statistics, but it’s real.

Also, many of the companies that hired fastest, especially in technology, have since laid people off. Those people do not have expanded government benefits to fall back on and are not negotiating new jobs from positions of power. American workers are also doubly threatened by cheaper migrant labor and, of course, by artificial intelligence.

Usually, when somebody tells you they feel a certain way, it’s bad form to tell them that they don’t, or that they shouldn’t. What they really mean is, “Sorry you feel that way,” and in the best tradition of Dr. Pangloss, patron saint of economists, this is the best of all possible worlds.