Work got the best of the Middlebrow this week and I missed my usual Friday morning post. There’s a lot of cultural stuff I want to tackle but this seems like a good opportunity to take on a short, yet important free speech topic.

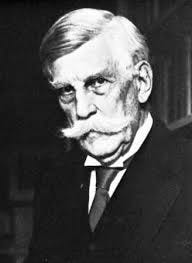

As the election approaches and the volume of Internet chatter rises, we’ll hear frequently that freedom of speech is never without its limits and that you can’t “yell fire in a crowded theater” because people will be trampled to death. Now, feel free to stop reading if you know this, but the phrase comes from a Supreme Court decision written by Oliver Wendell Holmes about a case that had nothing to do with anybody yelling fire in a crowded theater.

This isn’t esoteric. It’s on Wikipedia. It’s a metaphor Holmes used and, as you'll see, he used it inaptly. But, it is a good quote, its imagery is evocative and it is repeated a lot as a way of saying that there are legal limits to speech, even under the first amendment of the United States Constitution.

The thing is, the metaphor that Holmes employed was almost hysterically inapt and it was used in service of a Supreme Court decision that I think most people would view as a grievous error. During World War I, Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer were convicted of violating the Espionage Act of 1917 by printing and distributing flyers telling young men drafted in the military to refuse to serve.

Schenck and Baer believed conscription violated the 13th amendment against involuntary servitude. The espionage act made it illegal to inspire insubordination within the military or to obstruct recruitment. They argued against their conviction on first amendment grounds and the Supreme Court sided with the government.

You might love, hate or be indifferent to what Schenk or Baer did, but more than 100 years later, I think most Americans would say that they were within their rights to hold and express anti-war and anti-draft views. Holmes believed they presented a “clear and present danger” to national security (another phrase that has entered the common language) but Schenk and Baer were clearly engaging in political speech, which is exactly what the first amendment is supposed to protect.

Holmes falsely equated political speech with intentionally harmful speech to uphold a conviction for activity that never should have been considered criminal or sanctionable by the government. His metaphor has since been divorced from the case, to support the idea that speech can and should be legally regulated.

From a civil liberties perspective, the Espionage Act, though now more than a century old, has long been controversial and abused to silence political dissidents and it is not as common sense accepted by people as the notion that it is dangerous to scream about fake disasters in crowded spaces.

Holmes’ point is that yes, speech can be regulated within the confines of the first amendment. He might have brought up libel or slander, which are punishable even in a free society. If in practice, we mean that speech can be regulated only in the most extreme cases where the speaker is causing real harm to innocent people, his metaphor works. But it’s hard to believe that the Supreme Court’s decision in Schenk meets that standard at all. That’s probably the most important thing to remember about the “yelling fire” standard — it was misapplied as soon as it came into existence.

When it comes to speech regulation, the risk is always, first and foremost, that authorities will go too far, as has been proven time and again.